Book Note: A Scene in the City of Oaks: Searching for Freedom after the Civil War, by G. Ward Hubbs

- May 27th, 2016

- by specialcollections

- in Book Notes, Guest Contributors

This post by Dr. G. Ward Hubbs is an addition to our series of Alabama book notes. Hubbs is an archivist and professor emeritus of Birmingham Southern College. He is the author of several books, including Guarding Greensboro: A Confederate Company in the Making of a Southern Community (University of Georgia Press, 2003). In this post he sets forth the salient points of his most recent work, Searching for Freedom After the Civil War: Klansman, Carpetbagger, Scalawag, and Freedman (University of Alabama Press, 2015).

Searching for Freedom recounts the circumstances surrounding the most widely known political cartoon of the post-Civil War era, an image that is commonly found in American history textbooks today. The book presents the lives of the four individuals depicted in that cartoon as they struggled with the great issues of their times. Instead of remaining satisfied with four short biographies, however, the book reconstructs the very different notions of freedom that drove each of the characters.

Searching for Freedom begins with a vivid description of a hot, dusty Alabama afternoon in August 1868. That was when four individuals crossed paths in Tuscaloosa. Dr. Noah Cloud, the newly elected state Superintendent of Public Instruction, was a scalawag (a white native-born Republican) committed to establishing a public school system open to both black and white. The Reverend Arad Lakin, a Methodist minister sent to Alabama to reestablish the national Methodist Church, had recently been elected president of the University of Alabama. Raised in New York, a Union veteran, Lakin was thus a carpetbagger. The editor of the Tuskaloosa Independent Monitor, Ryland Randolph, was also the leader of the local Ku Klux Klan. And Shandy Jones, a black barber and dabbler in real estate, was the leader of the town’s freedmen. Cloud and Lakin were in the City of Oaks, as Tuscaloosa was familiarly known, to reopen the University of Alabama, which the state had been struggling to rebuild since Union cavalrymen had burned it to the ground in the last week of the Civil War. When their attempts to assume leadership of the school were rebuffed, the two turned back and returned to their homes in Montgomery and Huntsville.

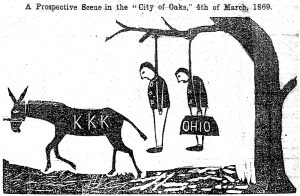

Four days later Randolph’s Independent Monitor printed a brutal political cartoon. Entitled “A Prospective Scene in the ‘City of Oaks,’” the stark woodcut depicted Lakin (with the carpetbag) and Cloud hanging from the branch of an oak tree with a donkey (standing for Randolph) emblazoned with the letters “KKK” walking out from under them. Printed two months before the presidential election of 1868, “A Prospective Scene” laid out “the fate in store for those great pests of Southern society—the carpetbagger and scalawag—if found in Dixie’s land” after a Democratic president took his inaugural oath. Although not depicted in the woodcut, the extensive caption threatened Shandy Jones with lynching as well. Here in one cartoon were the four iconic characters from Reconstruction: a Klansman, carpetbagger, scalawag, and freedman.

What led these four to this moment?

The Klansman Ryland Randolph (1835-1903) had an unusually disruptive upbringing, but two episodes stand out: the time he spent with his genteel agnostic uncle and the extended Caribbean tour he took with his father, a high-ranking Navy officer. The former left the young Randolph convinced that the whole idea of God was ridiculous. The latter reinforced his belief that the natural and proper station of the black race was slavery. Back in Alabama, Randolph rubbed elbows with many secessionist firebrands. His role in the Civil War was unexceptional despite serving under Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would later found the Ku Klux Klan.

The end of the fighting left Randolph without prospect or purpose. He found both when he purchased a newspaper in Tuscaloosa, which he immediately turned into a mouthpiece for opposition to social equality and the Republican Party. The newspaper’s motto, “The White Man—Right or Wrong—Still the White Man!” said it all. Every issue printed editorials urging citizens to stand up to the freed people. And Randolph did not limit his invective to print. On the streets he confronted any black man who refused to defer to a white man, and backed up his words with bullets.

Reopening the University of Alabama was a critical partisan issue, for in the hands of the university’s professors lay the state’s hopes for its future—as well as responsibility for assigning blame for the carnage of the 1860s. Cloud and Lakin embodied a nightmarish future, to Randolph’s way of thinking. Upon their arrival he summoned the Klan and published his cartoon. But Northern newspapers reprinted it by the hundreds of thousands, warning readers of what would happen if the Republicans lost the November presidential election. Democrats tried to dismiss it as a joke, but the damage had been done. The Republicans won the 1868 presidential election.

Ryland Randolph’s violent behavior in defense of former Confederates would be easy to dismiss as the unrestrained outpouring of an unprincipled racist. But Randolph’s behavior exhibited a consistency that flowed from his rejection of God and his concept of the People’s (read white people’s) freedom. Without the constraint of religious principles, he viewed the post-war as a brutal time of trials, in which freedom was the endpoint of a zero-sum game. Thus Randolph and his allies believed that they had to be ever vigilant lest their freedom be lost to usurpers. To them, that meant carpetbaggers, scalawags, and the freed people. Randolph was convinced that these opponents were trying to impose an unnatural order on the People—and he concluded that he was empowered to resist them by any means.

While Ryland Randolph was born into Southern wealth, the carpetbagger Arad Lakin (1810-1890) was born into rural poverty. And while Randolph renounced God when he came of age, Lakin embraced the Almighty. He even entered the ranks of the Methodist clergy and during the Civil War served as chaplain to an Indiana regiment.

After the war, the Bishop of Ohio (hence the “Ohio” on the carpetbag portrayed in the cartoon) sent Lakin to Alabama as a missionary for the national Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC). The latter had been excluded from the state since the 1840s, when the denomination had split over slavery. He plunged into his work establishing churches all over north Alabama. His primary constituencies were the poor upland whites and the freed people—those, in other words, who had remained loyal to the Union. In the process, he became active in Republican politics.

The Ku Klux Klan targeted Lakin, not only in the political cartoon but literally. He spent months in the mountains eluding their grasp. On several occasions he barely missed being shot or captured. His long and detailed testimony before the congressional committee investigating Klan activity provides an unparalleled look at these events.

Meanwhile, Lakin’s efforts to establish a biracial MEC in Alabama met with mixed results. He did succeed in creating the Alabama Conference of the MEC in 1867. But white Methodists resisted worshipping alongside black Methodists, and the latter were increasingly drawn to all-black denominations, where they could have a stronger voice. Lakin’s funeral would be preached in a black church that he had founded

Like Randolph, Lakin was empowered by his understanding of freedom; but in this case it was Christian freedom. Protestants often trace their understanding back to Martin Luther’s 1520 essay, On the Freedom of a Christian. There Luther makes an extraordinary statement: “We are free, subject to no one; we are servants, subject to all.” Christian freedom, in other words, involves severing certain bonds—to self and material goods—and appropriating new bonds—to serve God and others. Man was born in chains—to sin—but can be freed to liberate others. Lakin’s life embodied Christian freedom.

Having earning his M.D. in Philadelphia, the scalawag Noah Cloud (1809-1875) nonetheless gave up medicine to plant cotton in east Alabama. One day he observed that his neighbor’s cotton was far superior to his own. The reason was obvious—more fertile soil—and with that, Cloud dedicated his life to promoting scientific agriculture to skeptical Southern planters.

Dr. Cloud began publishing articles and attending agricultural conventions with the fervor of a convert. He started his own journal and rose to become the South’s most renowned scientific agriculturalist. In the process, his efforts won praise from many who would become leaders in the Confederacy. Yet Cloud, a Whig, showed no signs of supporting secession. His Confederate military service consisted of being a member of a “board of examining surgeons” in Savannah.

Dr. Cloud ran for political office after Appomattox—but as a Republican. This was entirely consistent with his Whiggish background but entirely at odds with his former Democratic contemporaries. He won office as Superintendent of Public Instruction and proceeded to create a modern public school system open to all children—black as well as white. This, of course, enraged the former Confederates even more and explains why his arrival with Lakin in Tuscaloosa provoked the cartoon.

The key to understanding Dr. Cloud’s pursuit of scientific agriculture and his later entry into general education lies in his Whiggish intellectual and moral roots. Whigs believed that the educated, prepared, and self-disciplined—free individuals, in other words—could escape ignorance, hidebound habits, and the limitations of birth. Whiggish freedom is thus ordered, purposeful, and placed in our own hands. Whiggish freedom is a ceaseless task of self-creation. Whether pushing for scientific agriculture or an educational system open to all, Cloud preached freedom as liberation from the shackles of ignorance.

Born a slave but freed as a child, Shandy Jones (1816-1886) made his living as a barber, the most lucrative and prestigious profession in which free blacks in the South could engage. He did well in Tuscaloosa, not only raising a large family but amassing a great deal of wealth through real estate investments.

He remained unsatisfied. Beginning in the late 1840s, Jones became Alabama’s leading black advocate for colonization to Liberia. Liberty in Liberia: therein, he believed, lay hope. In Africa black people could create their own schools, worship in their own churches, come and go as they wished. No matter how well Jones did, he could never rest easy; for Jones represented the worst of white fears—proof that black people could, in fact, govern themselves. As such, Jones was under constant legal and social sanctions.

With the end of slavery, Jones became actively involved in founding churches and schools. He continued to support colonization, but black suffrage and the election of new Republican state officials turned his hopes to changing Alabama. He won election to the state House of Representatives from Tuscaloosa. The election of Dr. Cloud and the appointment of Lakin held special significance because the two had both the power and commitment to create biracial schools and churches, and Jones believed that his son would become the first black student at the University of Alabama—a century before that milestone would be reached. His dream quickly died as Ryland Randolph and the Klan forced Jones to flee Tuscaloosa for Mobile, where he ended his days as pastor of the Little Zion Church.

As a black man and former slave, freedom had an immediate and physical sense for Jones that the other three could only imagine. His bondage had been dictated by the color of his skin and the status of his enslaved mother; but his freedom depended on mere ink on paper. What had been given could be taken away. The possibility of its arbitrary cancellation must have hung over his head. Hence it is small wonder that Shandy Jones looked for freedom in another place, ultimately in the freedom of Hope.

The essence of Searching for Freedom can be found in the book’s last sentence: “Everyday life is saturated with ideas, values, and meaning.” Indeed, those deeply held convictions about freedom held by these everyday people, long forgotten, are with us still.