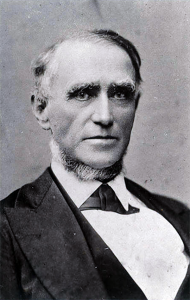

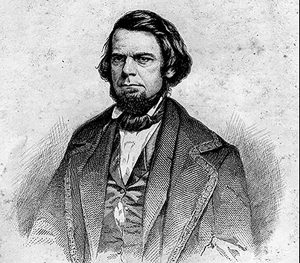

Teacher and Pupil: Henry Tutwiler and William Russell Smith, 1869

- May 26th, 2020

- by specialcollections

- in General

In November 1869, Henry Tutwiler sat down to review (for the Mobile Register) a translation of the fifth book of the Iliad. A slender volume titled Diomede: From the Iliad of Homer,[1] it was the work of his former pupil William Russell Smith, who had studied under Tutwiler at the University of Alabama more than thirty years earlier. The two men had been friends ever since. Indeed, Tutwiler figured largely in Smith’s recollections of Tuscaloosa days, as a “delicate stripling of a youth,” a recent graduate of the University of Virginia who was so learned that he was “a whole faculty within himself.” Evidently Tutwiler’s manner as a professor was so appealing that “every boy fell absolutely in love with him” and felt for him “real affection, which suffered no diminution by the lapse of time.”[2]

While Tutwiler carried out several duties during his years (1831-1837) at the University, he was primarily a Classics professor. Smith has left us a memorable snapshot of his teacher: “As one of his peculiarities, Professor Tutwiler was seldom seen in or out of the school-room without having a small volume in his left hand. He had a diamond edition[3] of the ancient classics, and carried about with him either Virgil, Horace, the Anabasis, Iliad, Cicero, Terence, or Euripides. These were his quiet companions, from whom he seemed to be inseparable.” Smith went on to say that Tutwiler “was never without a pencil; and would stop in his walks, under the shade of an oak, and enrich the margin of his book with some useful hint or scholarly annotation.”[4]

In the decades since their shared time in Tuscaloosa, each man had enjoyed a distinguished career: Tutwiler as the founder of the Greene Springs School, the state’s most celebrated private academy; and Smith as a lawyer, U.S. Congressman, and author of legal treatises, works of fiction, plays, and poetry.[5] In his review of Diomede, Tutwiler recognized Smith’s status as an important public figure by including him in a list of European statesmen and crowned heads who were devoted to the Greek and Roman classics. Tutwiler was happy, he added, “to welcome any effort to throw off the reproach under which we, of the South especially, have labored, of a neglect of classical literature.”[6]

Tutwiler was aware that Smith had been laboring over the Iliad for some twenty years. Yet seeing a portion of that work “gotten up in the best style of Appleton’s” awoke in him memories even older.

“We well remember,” Tutwiler wrote, “how, when a lad at the University of Alabama,” Smith “was in the habit of handing in as exercises, poetical translations of the Latin poets.” Conjuring up (for modern readers) images of class files carefully stored away at Greene Springs, he declared that “we could, even now, lay our hands upon some of these juvenile productions.” Tutwiler understood that Smith’s translation was a true labor of love, and he quoted a passage from Diomede in which Smith declared that his pleasure in the work “has been long continued, making many a night glorious.”[7]

The Iliad is Homer’s telling of episodes from the Trojan War—beginning with an ugly quarrel in which Agamemnon, leader of the Greek expedition, offends the supreme Greek warrior Achilles. Their temper tantrums bode ill for Greeks and Trojans alike. Book five presents the exploits of the Greek hero Diomedes, who, inspired by the pro-Greek goddess Pallas (Minerva), rages like a berserker among the forces of Ilium (Troy), killing several notable warriors. In the process we meet many of Homer’s cast of mortals and immortals and see much of the home life of the latter. Such is Diomedes’ divinely granted power that in the course of his rampage he wounds Venus, goddess of love, and Mars, the god of war. Book five ends with Mars safely back in Olympus, his wounds healed.

As for Smith’s approach to Homer’s text, Tutwiler reported that his former pupil made use of the “Pentameter iambic or Heroic couplet.” In this Smith was following the lead of Alexander Pope, the celebrated eighteenth-century English poet, who had published his translation of the Iliad in installments during the 1710’s.[8] Tutwiler gave Smith credit for being a more faithful translator than Pope; and he couldn’t resist passing on an anecdote in which Pope, having “pressed the great Greek scholar Dr. Bentley, for his opinion of the work,” received the following answer: “It is a very pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer.”[9] But Tutwiler was ever judicious, and he admitted to the Mobile Register readership that it was to Pope’s “fascinating version” that he owed his own “early familiarity with the old Greek bard.”[10]

Tutwiler’s personal standard for accuracy in translation was the blank verse Iliad of Lord Derby,[11] who could afford to be precise because he “was not hampered by the fetters of rhyme.” Smith, according to Tutwiler, did not quite measure up to Derby, in part because he was guilty of an occasional paraphrase. Moreover, “If we were disposed to criticize [Diomede] closely, we could probably point out some errors which have escaped the author’s notice, but which will, no doubt, be corrected when the whole is published.” Tutwiler understood that Smith’s purpose was “to feel the public pulse with this book, and if it prove a success, to publish the whole.”[12]

Overall, Tutwiler praised his former pupil without showing too much favoritism. He encouraged Smith to finish his project and concluded that its completion “will do credit to him and to his native State.” Smith did follow through to the extent that in 1871 and 1872 he published editions of A Key to the Iliad of Homer, for the Use of Schools, Academies, and Colleges.[13] Smith described it as “my school arrangement” of Homer’s classic. Tutwiler received a copy, and responded that “if a boy were to read the parts you have published” and “make a lexicon of all the words contained in them,” he would “find no difficulty in reading the whole of Homer.” He promised Smith that he would “try it in the next class I have in Homer.”[14]

Tutwiler’s Mobile Register review had concluded with some excerpts from Diomede. At a point at which a phalanx of Greek fighters opposes a force of Trojans led by the great Aeneas, Agamemnon gives encouragement to his men:

Now Agamemnon, king of men appears;

His voice inspires, as his presence cheers;

“Be steadfast, fellow warriors; know his date

Of life is short who dreads the shafts of fate;

The dastards who, in fear of danger fly,

Are doubly doomed, for twice they have to die;

By terror, once—for fear of death is death—

Then by the sword, that cuts the coward’s breath.

Fear not to die; fear not a Trojan’s face,

But fear the eternal badges of disgrace;

Who dies a coward, forfeits life and fame;

Who dies a soldier, leaves his child a name.”

Then Homer and his translator show how Juno and Minerva (pro-Greek goddesses) prepare to enter the fight:

Then Juno dressed, in trappings rich and gay,

Her panting war-steeds for the coming fray.

Her own white hands the golden harness spread

Impatiently, and forth the coursers led.

Hebe adjusts the car with ready zeal

And mates each axle with its fellow wheel. . .

Meantime Jove’s daughter on the Olympian [floor[15]]

In haste threw off the ambrosial robe she wore;

Virgin apparel, by her fingers wove

Fit for a princess in the courts of love,

But not for warriors; then the goddess laced

The Thunderer’s glittering corslet to her waist,

And armed complete to shake the battle field

She seized and shouldered Jove’s terrific shield![16]

With these lines Tutwiler ends his article, signing himself “H.T., Greene Springs.”

PMP

[1] William Russell Smith, Diomede: From the Iliad of Homer (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1869).

[2] William R. Smith, Sr., Reminiscences of a Long Life: Historical, Political, Personal, and Literary (Washington, D.C.: William R. Smith, Sr., 1889), 228-229.

[3] The British publisher William Pickering produced “Diamond Editions” of Classical authors, in addition to the works of Shakespeare, and Milton. These were very small volumes printed in what was listed as “48vo,” which means that they were even smaller than the duodecimo (12vo) pocket-sized books of the time. See Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, From January to June, 1831, CI [101] [London: J. B. Nichols & Son, 1831], 12.

[4] Smith, Reminiscences, 229.

[5] Generally, see Thomas M. Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography (Chicago: S,J, Clarke Publishing Company, 1921), IV: 1597-1598 (Smith), and IV: 1694-1695 (Tutwiler). See also Benjamin Buford Williams, “William Russell Smith,” in Encyclopedia of Alabama [online]. For Smith’s legal and political works see Paul M. Pruitt, David I. Durham, and Michael H. Hoeflich, Law and Miscellaneous Works: The Lives and Careers of Joel White and Amand Pfister, Booksellers and Publishers (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama School of Law, 2019), 14-17, 43, 73-76, 78-81.

[6] H.T., “Poetical Translation of Homer’s Iliad, by Wm. R. Smith of Tuskaloosa, Ala.” Mobile Register, November 13, 1869. Any quoted passages below, unless otherwise identified, are from Tutwiler’s article.

[7] Tutwiler is quoting from Smith, Diomede, 52.

[8] Alexander Pope, translator, The Iliad (London: W. Bower for Bernard Lintott, 1715-1720).

[9] Dr. Bentley was Richard Bentley (1662-1742); see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Bentley Bentley was widely considered a great scholar as well as an important administrator at Cambridge. He was, however, a difficult personality. On the latter point see a work with which Tutwiler and Smith might have been acquainted—James Henry Monk, Life of Richard Bentley, D.D., Master of Trinity College and Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Cambridge (London: C.J.G. & F. Rivington, 1830), 228 and passim.

[10] During Tutwiler’s boyhood, a century after the first publication of Pope’s Iliad, the latter work was available in two duodecimo volumes published by Chiswick of London, c. 1822. One wonders if the boy Tutwiler often had one such small volume in his hand. See above at note 4.

[11] This was a recent edition, published in London in 1864. For an American edition see Edward, Lord of Derby, The Iliad of Homer Rendered into English Blank Verse, 2 volumes (New York: Scribner, 1865).

[12] For his part, Smith had no artistic qualms about publishing a single “book” of the Iliad, since he maintained that the various units of the work had been chanted as discrete poems from the time of their first composition until at least the time of Lycurgus (c. 800s BC). Smith dated the compilation of a coherent single Iliad to the lifetime of Pisistratus of Athens (died 527 BC). See Smith, Diomede, iii.

[13] The 1871 edition was self-published in Tuscaloosa. The 1872 edition was published in Philadelphia by Claxton, Remsen, and Haffelfinger. The latter contained, per WorldCat, “the text of the first and sixth book[s], a large portion of the fifth, and a few select passages from the second.”

[14] Smith, Reminiscences, 233.

[15] Misprinted in the Register as “flow.”

[16] Tutwiler copied these verses from Smith, Diomede, 32-33 and 42-43.