The Knights Templar: an Exhibit from our Collections

- October 12th, 2015

- by specialcollections

- in Collections, Exhibits

Who were they?

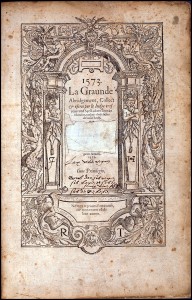

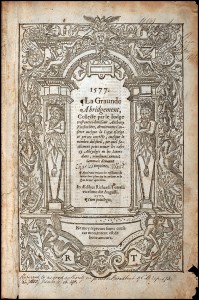

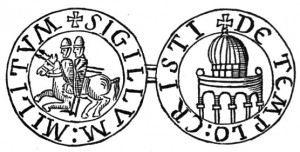

The Knights Templar was a secret religious order established in 1119-1120 in the aftermath of the First Crusade and officially acknowledged by the Roman Catholic Church in 1129. The order was established to ensure the safety of Western pilgrims to the Holy Land; but its military successes, the prowess of its warriors, and eventually, the banking services it provided made it influential in Western Europe and within the Church. Over the centuries, rumors have swirled about the Templars and the great wealth that they acquired. In particular, they were thought to have discovered and protected the legendary treasures of Christianity: the Holy Grail, the Ark of the Covenant, pieces of the True Cross, and other relics. Such tales have inspired many conspiracy theories about the Order, including Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum and Dan Brown’s cult phenomenon The Da Vinci Code.

What happened to the Order?

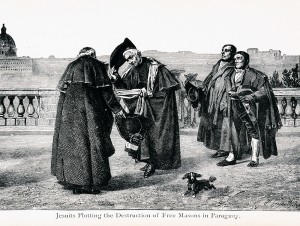

Once the Holy Land finally fell to the Muslims in the late 13th century, Papal and royal support for the Order declined. The Templars had become increasingly powerful as property owners and bankers to the kings and nobility of Europe. Likewise, rumors about the secret and possibly heretical rituals of the Order circulated throughout Europe until Pope Clement V ordered all European monarchs to arrest the Knights and seize Templar assets in 1307. Scores of Templar knights were tortured, forcing them to admit, often falsely, to heretical behavior. Pressured by King Philip of France, who was heavily in debt to the Templars, Pope Clement dissolved the Order in 1312.

How is it perceived now?

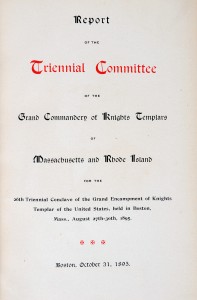

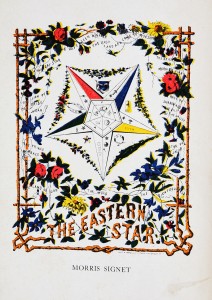

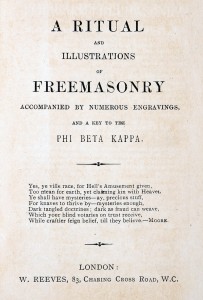

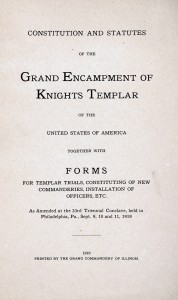

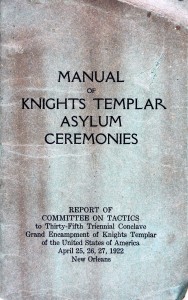

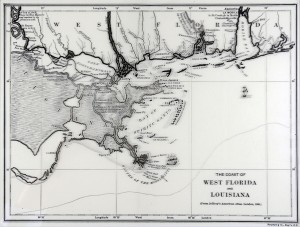

Although the Order was dissolved by the Church and vilified by all Western monarchies in the 14th century, the Knights Templar has survived to this day in other forms. Most notably, the York Rite of the Order of the Knights Templar remains an important adjunct of Freemasonry in both America and Western Europe. In the nineteenth century the Masons established Templar orders in almost every American state and held both national and local conventions. The rituals of the medieval Knights Templar are preserved as Masonic rituals and are described with great detail in Freemason ritual books. The Order continues to be a great philanthropic society in the United States.

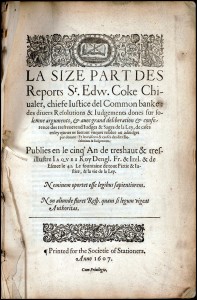

In Great Britain, the Templar aura lives in the education of lawyers. Two of the four Inns of Court in England are the Inner Temple and Middle Temple—named for the Templar buildings in which these Inns are housed. Scores of students have and continue to study in these Inns and remain members—Templars—as they begin their law careers. Even some of the authors of the U.S. Constitution were educated in these Inns, inspiring them to form American counterparts to the British Inns of Court.

Internationally, the Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem (not affiliated with Masonic Templars) has recently achieved NGO status from the United Nations as a charitable organization.

New Developments

In 2001, a document was found in the Vatican Secret Archives; incorrectly filed, it had lain undiscovered for centuries. It provided evidence that Pope Clement had absolved the Templars of heresy in 1308—four years before excommunicating them under French pressure. The Vatican published this discovery—known as the Chinon document—in October 2007. Thus the Church now maintains that the 14th century persecution of the Knights Templar was unjust. The Order was not heretical in any way, but was dissolved for political reasons.

This Exhibit

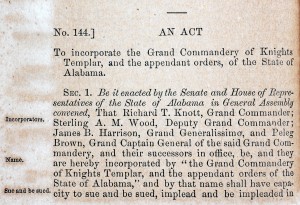

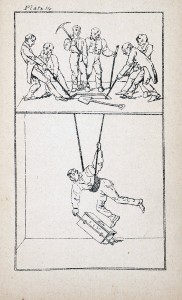

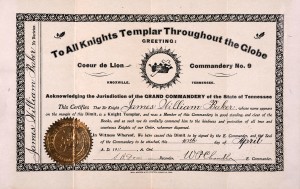

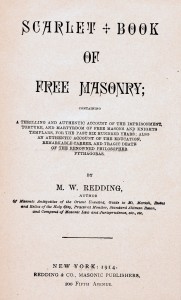

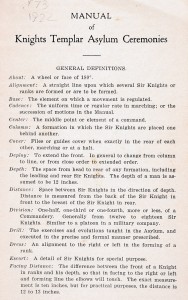

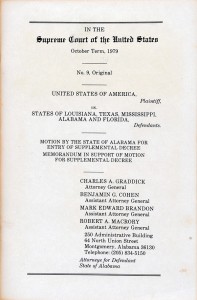

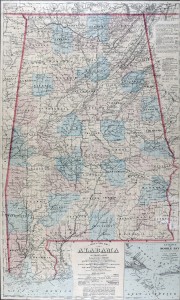

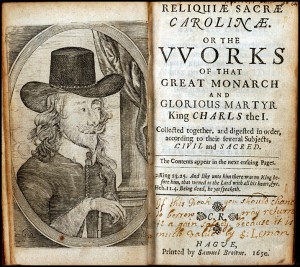

The Knights Templar is represented in the Bounds Law Library’s collections mostly in the form of nineteenth and early twentieth century Masonic materials. Many rituals of the medieval order are depicted—often in great detail—in these works. Selections from our collection include manuals, bylaws, rituals, an “Authentic Account of the Imprisonment, Torture, and Martyrdom of Free Masons and Knights Templars…,” as well as an 1861 Alabama legislative act incorporating the Grand Commandery of Knights Templar. The exhibit also features an original document; a 1911 certificate of knighthood from the Grand Commandery of the state of Tennessee.

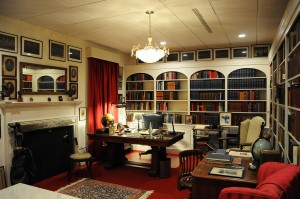

The Bounds Law Library’s Templar exhibit is located in the John C. Payne Special Collections Reading Room and we welcome visitors during regular Special Collections hours. Chainmail coif, swords, and shields must be checked at the circulation desk!