Alfred’s Doombook: The Anglo-Saxon Foundations of Magna Carta

- December 2nd, 2019

- by specialcollections

- in Guest Contributors, Uncategorized

From time to time we like to post historical essays written by recent Law School graduates. Today’s post is a work of intellectual history by Christopher Collins, a 2019 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Law who is currently a graduate student in the UA College of Communication and Information Sciences. Chris is working on his MLIS. The title of his essay is “Alfred’s Doombook: The Anglo-Saxon Foundations of Magna Carta.”

Alfred’s Doombook: The Anglo-Saxon Foundations of Magna Carta

Magna Carta might often be misunderstood, but far worse is that King Alfred’s Doombook[1] is so neglected. A.E. Dick Howard wrote that Magna Carta “became and remains today one of the great birthrights of men who love liberty.”[2] But on June 15, 1215, it had nowhere near the significance it has assumed in recent years––its force of law actually declined over the next several centuries.[3] J.C. Holt even opened his magnum opus on the Charter with the statement that “Magna Carta was a failure.”[4] And yet we know it as Magna Carta––the Great Charter; but it was less an act of greatness than a preservation of the status quo[5] and perhaps even a bad-faith baronial power grab.[6]

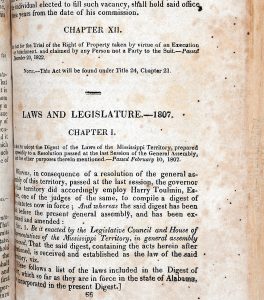

Much of Magna Carta’s influence derives from the fact that it was thought for many centuries to be the oldest extant consolidated written statement of English law.[7] Even after the rediscovery of the old Anglo-Saxon laws, Magna Carta continued to be worshipped as “a sacred text, the nearest approach to an irrepealable ‘fundamental statute’ that England has ever had.”[8] King Alfred’s Doombook, however, is the oldest extant consolidated written statement of English law, and it is time to rediscover it as the true founding document of Anglo-American legal heritage.[9]

This paper aims to show that while Magna Carta is rightfully revered as “a foundation stone of English and American legal rights,”[10] it is not the origin of our liberty-loving rights. Magna Carta is rather a later stone placed upon an Anglo-Saxon legal foundation started by Alfred’s compilation of laws, the Doombook. King Alfred compiled these laws toward the end of the ninth century.[11] He consolidated longstanding customs and practices from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and added Biblical authority.[12] Alfred’s goal in promulgating his Doombook aimed at uniting the English amid existential threats posed by large-scale Viking invasions. And the English kings seemed to base their authority partly on continuity with their predecessors––the legitimate king preserved the traditions of his predecessors, and this is the topic of Part I of this paper.

Kings Alfred and John actually had a great deal in common, as will be discussed in Part II, though history has been kind to the former and critical of the latter. Both were unlikely kings, favored by their fathers and dutiful to their brothers. But Alfred inherited a kingdom on the verge of annihilation whereas John would be crowned king of an efficient and almost automated governing apparatus.[13] This apparatus owed much to the reforms of John’s father, Henry II, but the system itself was built on the works of Alfred and the laws of his Doombook.

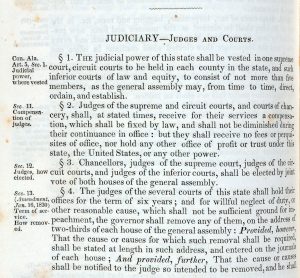

Parts III and IV will discuss Magna Carta and the Doombook. Part III will mention two fields that show no Anglo-Saxon precedent: the Charter’s “immediate use” provisions and the introduction of environmental law into the realm of English legislation. Part IV will discuss four common threads that show a continuum between Magna Carta and Alfred’s Doombook. These threads involve the regulation of customs and immigration; the rights of widows and the freedom of marriage; the idea that the king is not above the law and his need to seek counsel from his subjects; and the idea of due process and the equal application of the law of the land.

Every influence English law encountered, including Norman influence, has left an imprint on its character, but the Conquest merely wove itself into the established Anglo-Saxon fabric.[14] England did not begin anew when William and his Normans conquered the island.[15] The Anglo-Saxon system persisted and continued to provide the matrix within which English law would grow.[16] Magna Carta, like many famous tapestries from the Norman and Angevin era, is made of intricate stitching. But the first stitches to Magna Carta were not Norman or Angevin––they were Alfred’s.[17]

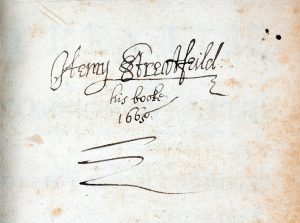

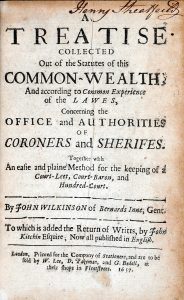

By this time there had been no king on the throne since the execution of Charles I in 1649. Puritans and supporters of Oliver Cromwell’s “Protectorate” were very much in control of the nation. They expected sheriffs and other officials to enforce punitive laws based, more or less overtly, on Puritan notions of morality. Consider this passage, from page 174 of Wilkinson’s book:

By this time there had been no king on the throne since the execution of Charles I in 1649. Puritans and supporters of Oliver Cromwell’s “Protectorate” were very much in control of the nation. They expected sheriffs and other officials to enforce punitive laws based, more or less overtly, on Puritan notions of morality. Consider this passage, from page 174 of Wilkinson’s book: