BRUTUS, CASSIUS, JUDAS, AND CREMUTIUS CORDUS: HOW SHIFTING PRECEDENTS ALLOWED THE LEX MAIESTATIS TO GROUP WRITERS WITH TRAITORS

- June 4th, 2021

- by specialcollections

- in Guest Contributors

The editors of Litera Scripta are aware that we live in troubled times. At home we face political divisions more intense than any since the American Civil War. Meanwhile, across the globe, authoritarian regimes have taken a page from George Orwell and turned disinformation into an evil form of art. The editors are confident, however, that there is very little that is new under the sun. That said, we should study the past for clues to present predicaments; and one cannot do better in this regard than to study the legal history of imperial Rome. There we see the “cult of personality” carried to its highest degree, resulting in the erosion—sometimes gradual, sometimes very rapid—of freedoms that Romans had taken for granted. This erosion of rights affected the state’s legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens. Eventually it affected the state’s ability to function.

These themes are present in Hunter Myers’ “Brutus, Cassius, Judas, and Cremutius Cordus: How Shifting Precedents Allowed the Lex Maiestatis to Group Writers with Traitors.”[1] This fine work of scholarship shows how the Roman concept of Maiestas (the “majesty of the state”) developed over time. It concludes with persuasive evidence that the Emperor Tiberius[2] twisted that element of Roman law to his own advantage—in the process corrupting the Senate, the courts, and the public itself. More dramatically, Mr. Myers shows us that Tiberius presided over his own descent into corruption—in his case marked by hypersensitivity to criticism, openness to malicious prosecutions, a thirst for vengeance, and other aspects of cold-hearted paranoia.

Hunter Myers is a member of the Class of 2022, University of Alabama School of Law and the forthcoming Editor-in-Chief of the Alabama Law Review.

[1] Honors Thesis, University of Mississippi, 2018.

[2] Ruled 14-37 AD.

BRUTUS, CASSIUS, JUDAS, AND CREMUTIUS CORDUS:

HOW SHIFTING PRECEDENTS ALLOWED THE LEX MAIESTATIS TO GROUP WRITERS WITH TRAITORS

By

Hunter Myers

A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment

of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College.

Oxford, Mississippi, May 2018

Advisor: Professor Molly Pasco-Pranger

Reader: Professor John Lobur

Reader: Professor Steven Skultety

© 2018

Hunter Ross Myers

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Pasco-Pranger,

For your wise advice and helpful guidance through the thesis process

Dr. Lobur & Dr. Skultety,

For your time reading my work

My parents, Robin Myers and Tracy Myers

For your calm nature and encouragement

Sally-McDonnell Barksdale Honors College

For an incredible undergraduate academic experience

ABSTRACT

In either 103 or 100 B.C., Saturninus invented a concept known as Maiestas minuta populi Romani (diminution of the majesty of the Roman people) to accompany charges of perduellio (treason). Just over a century later, Tiberius used this same law to criminalize behavior and speech that he found disrespectful. This thesis offers an answer to the question as to how the maiestas law evolved during the late republic and early empire to present the threat that it did to Tiberius’ political enemies. First, the application of Roman precedent in regards to judicial decisions will be examined, as it plays a guiding role in the transformation of the law. Next, I will discuss how the law was invented in the late republic, and increasingly used for autocratic purposes. The bulk of the thesis will focus on maiestas proceedings in Tacitus’ Annales, in which a total of ten men lose their lives. The most striking trial that will be investigated is the one involving Cremutius Cordus, who praised Brutus and Cassius, referring to them as the “Last of the Romans.” However, does this make him a traitor who belongs in Dante’s ninth circle along with Brutus, Cassius, and Judas?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Prologue

Roman Precedent and Exempla

The Application of Roman Precedent

Precedent in the Late Republic

Augustan Exempla

The Rewriting of Precedent under Tiberius

Inventing Maiestas

Origins of the Law – Perduellio

A Descendant of Perduellio – Maiestas

Two Test Cases: Caepio and Norbanus

From Varius to Sulla

Caesar’s Law and Motivation

Maiestas in Tacitus’ Annales

Examining Tacitus

Maiestas and Augustan Precedent in The Annales

Two Preliminary Tests Under Tacitus

Marcellus

Appuleia Varilla

Germanicus and Gnaeus Piso – Maiestas Turns Deadly

The Creep of Maiestas and Informers

Two Proceedings in 22 A.D., Maiestas Targets the Powerful

Gaius Silius, Calpurnius Piso, and the Protection of Informers

Cremutius Cordus, The Apex of Tyranny

The End of the Reign of Tiberius

Epilogue

Bibliography

Prologue

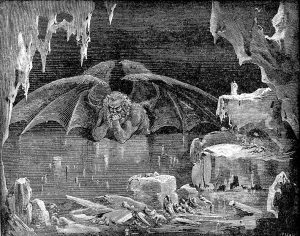

That upper spirit,

Who hath worst punishment, so spake my guide,

“Is Judas, he that hath his head within

And plies the feet without. Of th’ other two,

Whose heads are under, from the murky jaw

Who hangs, is Brutus: lo! How he doth writhe

And speaks not. The other, Cassius, that appears

So large of limb. But night now reascends;

And it is time for parting. All is seen. (Inf. XXXIV, 56-64)[1]

Dante vividly describes the ninth circle of hell, an icy section reserved for those who betrayed others in their life on Earth. A person who committed this type of act was, and still is today, truly considered the worst of the worst. Why is the concept of betrayal such a powerful one? Could it be due to the premeditation required to betray another person, or perhaps one imagines the damage that could be done if they themselves were betrayed?

Whatever the cause may be, the human race seems to be fascinated with the concept, as stories of treachery are as old as time itself. In Genesis Cain killed his own brother Abel, which constituted the first murder and first betrayal in the Abrahamic tradition.[2] When the Spartans held back the Persians at the “hot gates” of Thermopylae, they lost their lives due to the betrayal of Ephialtes (Hdt. 7.213).[3] Caesar was stabbed to death close to the Theatre of Pompey by a group of senators, led by the trusted Brutus and Cassius (Plut. Vit. Caes. 66).[4] Some seventy years later, Judas would betray Jesus, leading to his crucifixion.[5]

Around the same time as Judas’ actions, Cremutius Cordus was accused of treason for his written account of Roman history. His accusers specifically pointed at one phrase in which he labeled Brutus and Cassius as “the last of the Romans”. Knowing that his guilt and execution were certain, Cremutius Cordus took his own life. However, is there any resemblance between his actions, and those of Brutus, Cassius, and Judas?

Dante places the unholy triad of Brutus, Cassius, and Judas in the center of his Inferno, eternally trapped in the jaws of Lucifer himself. Their treason is inarguable, as Brutus and Cassius directly participated in Caesar’s murder, and Judas handed Jesus over to the authorities who despised Jesus. They all betrayed the leaders of their time, one being secular, the other being spiritual. Brutus and Judas both betrayed a close friend. In virtually every society that has ever inhabited the Earth, treason is one of the worst possible offenses, and one that both the government and the populace will not tolerate. This sentiment is what allowed the Roman charge of maiestas minuta populi Romani (diminution of the majesty of the Roman people) to evolve from an accompaniment to a treason charge to a forced suicide preceding, or a death sentence following, a show trial under the emperor Tiberius. Saturninus, a tribune of the plebeians, originally proposed the law to prosecute people who he believed had diminished the majesty of the Roman people. However, as Rome shifted from Republic to Empire, especially under Tiberius, the law became a convenient tool to prosecute, and execute, anyone at the whim of the emperor. Eventually, the maiestas law extended to persons who used contentious words, such as Cremutius Cordus. The maiestas law labeled speech as sedition, turned writers into traitors, and led to the death of many who dared to use the wrong words.