UA Women in the Law School

- June 17th, 2024

- by specialcollections

- in 150 Years of UA Law History, Guest Contributors

As part of our series that highlights 150 years of our law school’s history, Litera Scripta welcomes this contribution celebrating UA Women in the Law School. Author Jenna M. Bedsole is a 1997 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Law and works as a corporate attorney in Memphis, Tennessee. Ms. Bedsole directed and produced the documentary film titled “Stand Up and Speak Out” about 1936 UA Law graduate Nina Miglionico. As a woman, lawyer, and Italian-American, Miglionico was a pioneer in the mid-twentieth century Birmingham, Alabama legal community.

UA WOMEN IN THE LAW SCHOOL

“It’s great to be first, to be ‘one,’ it’s the two, three that come after you, that’s the telling thing.” Nina Miglionico (Class of 1936)

The Students

The University opened admission to women in 1893.[1] The first known woman law student at the University of Alabama School of Law was Louella Lamar Allen in 1907. Ms. Allen was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of Alabama on June 6, 1907 and was listed as attorney of record in Williams v. Finch, 155 Ala. 399, 46 So. 645 (1908). She does not appear to have practiced long after. She passed away in 1938.[2]

One year after Ms. Allen graduated, Maud McLure Kelly, who is considered Alabama’s first woman lawyer, graduated from the law school. Like many lawyers past and present, she was the daughter of an attorney. Her father, Judge McLure, presided over the Chancery Court in Anniston. Maud got a head start by reading law with her father, so it should have come as no surprise when she took the admissions test and scored well enough to be placed in the senior (second year) class. Not only did she graduate in a year, but she excelled: she ranked 3 of 33. But admission to the bar did not come easy. Ms. Kelly was admitted to the bar in 1909 but only after the legislature, in a bitterly divided battle, passed a special bill to change the wording of the Alabama Code from “presents his diploma” to “presents his or her diploma, and is permitted to try cases.” Undeterred, Ms. Kelly practiced in Birmingham from 1908 until 1917. To make clear to others she was a lawyer, she wore a black robe and mortarboard during her practice. She knew her worth, refusing to defend a client unless she was paid in advance. In 1914, she was admitted to argue cases before the United States Supreme Court – one of the first women in the South.[3] When her brothers were drafted to fight in World War I, she volunteered to work for the War Department.

Ultimately, she moved to Washington, D.C. where she worked for the Department of the Interior until 1924. She returned to Birmingham to practice. In 1931, she retired to care for her ailing mother. Twelve years later, she moved to Montgomery to work for the Archives of Alabama as a Historical Materials Collector. Over the next several years, Ms. Kelly cared for many members of her family: after her niece died, she took care of her four children and later she moved to Talladega to live with her brother. She continued to research her ancestors until she retired in 1956.[4] Ms. Kelly died of a stroke and complications from diabetes in 1973 at age 85. Although she never married, she dated well into her seventies.[5] Ms. Kelly was a “charter member of suffrage movement led by Patti Ruffner Jacobs.”[6] She was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 1990 and the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame in 2014. Every year, the Alabama State Bar honors a “female attorney who has made a lasting impact on the legal profession and has been a pioneer and leader within the state” with an award named after Maud McLure Kelly.

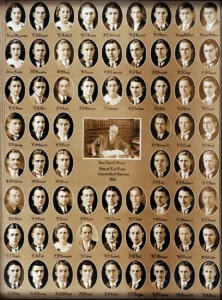

There were other women admitted to the law school, but the class of 1936 produced several powerhouse women lawyers.[7] Kathryn McDuff Rossback was among the members of that graduating class. She decided to practice because she felt limited by the Great Depression (1929-1939). She was from Tuscaloosa and practiced in Guntersville before moving, in 1937, to Washington, D.C. to work for the Department of the Treasury. She left the Treasury in 1951 after she got married and had a son. She returned to government practice in 1958 to work for the National Labor Relations Board. She returned to Tuscaloosa in 1973.

Irene Feagin Scott, a Union Springs native, was a classmate of Kathryn McDuff Rossback’s. She developed an interest in the law from her uncle who was a lawyer. Although Ms. Scott began in 1931, she paused her studies after her father died in 1932. Like her classmate, she also went to Washington, D.C., but she worked for the Internal Revenue Service’s Office of Chief Counsel. Once when asked if female attorneys faced fewer job opportunities than their classmates, she quipped, “there were no job opportunities for anyone.” She received an LLM in international and tax law from Catholic University and was ultimately appointed to the Tax Court in 1960 and reappointed in 1972. She became Senior Judge in 1982 and served until her death on April 16, 1997.[8]

Perhaps best known from that class was Nina Miglionico. Nina was born in Birmingham, Alabama to Italian immigrants.[9] She attended Birmingham City Schools and received her bachelor’s degree in Music from Howard College which later became Samford University.[10] Upon graduation, Nina had a choice: she received a scholarship to attend the University of St. Louis to further her studies in music or she could go to law school. She said she wanted to make a living, so she chose law school.[11] After law school, she looked for a job and received one job offer: for a position as a legal secretary. “That didn’t sound so hot,” she remarked and instead she opened her own law practice.[12] She and Robert Gordon shared an office so small that when a client arrived, one of them had to leave. Hers was a general practice – from family law to criminal law to civil litigation. She was a prolific speaker at local clubs about issues that particularly affected women.[13] She advocated for fairness in probate laws; she fought against the poll tax which adversely impacted women more than men; and she lobbied for the right for women to serve on juries.[14] As she did, her practice grew along with her notoriety.

She ran for the state house and lost but when Birmingham voted to change its form of government – from three city commissioners to the mayor/city council, Nina threw her name in the hat.[15] Out of 75 candidates for nine city council slots, she came in third.[16] In the runoff, hate literature surfaced – spewing racial epithets and anti-Catholic bigotry.[17] She came in ninth and was the only woman elected.[18] That City Council voted to reverse the City’s segregation laws, and on December 29, 1964, appointed the first African-American, Wilbur H. Hollins, to serve on a city board.[19]

Because she and another candidate had been the lowest two vote-getters, they had to stand for re-election in two years. Again, the hate literature resurfaced during her re-election campaign. On April 1, 1965, a bomb was placed on her front doorstep. Her 80-year-old father, who was living with her at the time, heard the ticking from the box left on the porch, reached in, pulled out the timing device, and threw it on the ground. It never detonated.[20] Nina went to work that morning – undeterred. She won overwhelmingly and continued to serve the city she loved for more than 20 years. At the age of 71, she decided not to run for re-election.[21] Miss Nina died on May 6, 2009 – the Alabama State Bar believes she was the longest serving solo practitioner in history. She was a woman of short stature and one of her city council colleagues once jested, “Never mess with a woman twice your age and half your height.”[22] The Birmingham Bar Association’s Women’s Section honors her legacy by awarding lawyers who have actively paved the way to success and advancement for women lawyers with the Nina Miglionico “Paving the Way” award.

When the Alabama Law Review was established in 1948, there were two women students who served on its first volume, Serena B. Colvin and Shirley T. Seale. In 1952, Carole Orr served as its Editor in Chief. Despite this progress, in 1951, 97 women were admitted to practice law in Alabama with 27 practicing.[23] 1.6 percent of the attorneys in Alabama were women; 98.4 percent were men.

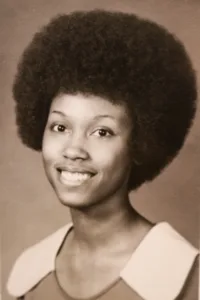

One of the first African American female students was Sue Thompson who earned her degree in 1974. Along with two other alumns from the law school, she founded the first Black law firm in Tuscaloosa. Thompson’s more than 40-year career has been spent advocating on behalf of low income and marginalized groups. She has been a fierce champion of local public education and has long collaborated with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund working to end desegregation in Alabama.[24]

Women students continued to thrive and following graduation, contribute to their communities. Consider Emily A. Brawner who graduated in 1949. She was a patent attorney, who moved back to Alabama from Ohio to take care of her mother. She worked at Redstone Arsenal and then later Bradley, Arant, Rose and White in 1955. She later worked for the Social Security Administration as a Claims Administrator.[25]

For the past several years, women have comprised a majority in the law school’s first year classes. Together, they share a characteristic of prior classes: “These women shared an attitude of being unaware that they couldn’t do anything they wanted to do.”[26] “They felt challenged, not intimidated.”[27] Those words described the women decades earlier but still ring true today.

The Bench

Women graduates have served as judges. For example, Phyllis Schneider Nesbit graduated in 1958 and moved to Baldwin County where she became a municipal judge for Daphne in 1964. Interestingly, she served as a judge before women were given the right to serve on juries.[28] In 1976, she was the first woman elected to serve as a trial judge in Alabama. She served Baldwin County until January of 1989.

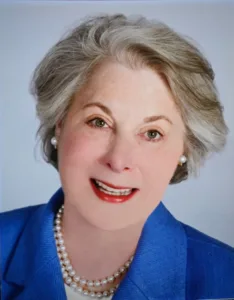

The first woman to serve on the Alabama Supreme Court was UA alumni, Janie Ledlow Shores. Justice Shores graduated from the law school in 1959. Born in Butler County (Georgiana, Alabama), she remembered growing up picking berries and potatoes.[29] Her family later moved to Loxley, Alabama in Baldwin County. There she learned, “We were all supposed to treat others as we wanted to be treated.”[30] She graduated from high school on a Friday in April of 1950, packed her bags, and boarded a bus to Mobile to look for a job. The very next day, she interviewed with Vincent F. Kilborn, a prominent lawyer who hired her as his legal secretary. She credited Mr. Kilborn for planting the seed to further her education – one day he told her “You have an uncanny feel for the law. You ought to go to law school.”[31] In 1953, she married Bill Ellzey and moved to Selma. While in Selma, she took classes towards her undergraduate degree. She vividly remembered that when Brown v. Board of Education was rendered. Her father-in-law gave her an ultimatum: join the White Citizens Council or she would no longer be part of the family.[32] She left the family the next day.[33]

Thereafter, she enrolled in the University of Alabama in a program that permitted her to finish her undergraduate degree and later attend law school. Ultimately, she received her undergraduate degree from Samford University. In law school, she was known for her summaries which were handed down from year to year. Reflecting upon her time in law school, Justice Shores stated she did not feel discriminated against because she was female.[34]

She graduated at the top of her law class, but due to her gender, no law firm would hire her.[35] Instead, she served as a judicial law clerk for Alabama Supreme Court Justice Robert T. Simpson. During her clerkship, she found she liked the work of a judge.[36] After working for Justice Simpson, she accepted a position as an in-house lawyer with Liberty National Life Insurance Company.[37] In 1962, she married Jim Shores, a lawyer in Tuscaloosa. Her daughter was born two years later.[38] She joined the Cumberland Law School faculty in 1964 as its first female professor, a position she held for eleven years.[39] The Dean of the Law School bragged she was the first female law professor east of the Mississippi.[40]

In 1972, she ran for an associate justice position but was defeated in a runoff. In 1974, she ran again. That time, she won.[41] When she won, she became the first woman ever elected to a state supreme court position and only the third woman to serve on a state supreme court in the nation. When asked why she ran, Justice Shores joked, “…The governor missed three chances to appoint me so I decided if I was ever going to get there I had to run for it.”[42] She decided not to run again in 1998.[43]

President Bill Clinton considered Justice Shores for nomination to the United States Supreme Court. Ultimately, that nomination went to Ruth Bader Ginsberg.[44] Justice Shores died on August 9, 2017. She was 85.[45] She once said, “I didn’t want to be the best woman lawyer in the State of Alabama. I wanted to be the best lawyer there was. So I feel that and maybe most women would tell you that women lawyers or women executives of any sort, they feel that they cannot afford to make any mistakes…I always prepared. Not just prepared, I was beyond prepared.”[46] The Alabama Law Foundation awards a scholarship in Justice Shores’ honor to a female law student and the Litigation Counsel of America awards the Janie L. Shores Trailblazer Award as well.

The Faculty

Marjorie Fine Knowles was born in 1939 in Brooklyn, New York. She attended Smith College where she received her undergraduate degree and received an LLB in 1965 from Harvard Law School. She was admitted to practice law in New York in 1966 and in Alabama in 1975. Later, in 1978, she became a member of the bar of the District of Columbia. Ms. Knowles became an Associate Professor at the law school from 1972-1975 – its first female faculty member. She taught evidence, sports law, conflicts and sex-based discrimination. She took a two-year leave of absence after President Carter appointed her to serve as the first statutory Inspector General for the Department of Labor in Washington, D.C. She returned to the law school in 1980 and in 1982 became the Associate Dean. Four years later, in 1986, she left Alabama to become Dean and Professor at Georgia State Law School where she served until 1991.[47] She was the first female law school dean in Georgia and the second dean in the school’s history.[48] She resigned at the end of the 1990-91 year.[49]

Dean Knowles died on September 24, 2021 at her home in Atlanta.[50] Dean Mark Brandon remarked about Professor Fine Knowles’ time at the law school, “Her most important contributions, however, were to the causes of civil rights and especially the status of women.” He added, “She helped to change the face and culture of the Law School, as the number of women studying law here increased almost six-fold.”[51]

Camille Cook was born in 1924 and she came from a family of lawyers. Both her father, Judge Ruben Wright of Tuscaloosa, and aunt, Inez Duke Searcy, were lawyers. Aunt Searcy graduated from the law school in 1929. Her brother and children became lawyers. Becoming a lawyer did not seem like an odd career for women to her; her entire immediate family for three generations had either been lawyers or had married them.

Mrs. Cook began law school during World War II – classes were held in professors’ offices because there were only 12 other students. In 1947, she graduated and one year later, she married fellow student Sydney Cook and moved to Auburn in 1948.

In 1971, Governor Wallace appointed her to serve on the Alabama Air Pollution Control Commission. She was the only woman selected. She taught business law at the University of Alabama for 18 years while raising four children. In 1968, she returned to the law school to serve as its Assistant Dean. There, she taught family law and children’s rights. “In 1976, she became first female tenured law faculty member.”[52] From 1972 to 1982, she worked for the Alabama Bar Institute, where she was tasked with developing a series of seminars to teach Alabama attorneys about the new Alabama Rules of Civil Procedure before their implementation in 1973. Alabama was the 10th state to require attorneys to have a certain number of CLE credits yearly.

She served for 6 years as a member of the Smithsonian Council in Washington from 1972-1978.[53] In 1991, she received the Outstanding Commitment to Teaching Award by the National Alumni Association, the University’s highest honor for teaching excellence. That award “recognizes dedication to the teaching profession and the positive impact these professors have had on their students.”[54] One student remarked “(Cook) has the ability to motivate one to wish to excel. Her high moral values serve as a standard to which we all strive to achieve.”[55] She died on February 20, 2018.[56]

When she retired from teaching in 1993, Law School Dean Nathaniel Hansford described her as “a woman of gracious wisdom and unbound spirit who has given back to the world manifold gifts.”[57] He added, “Cook was a ‘pioneer woman’ in a field which was traditionally dominated by men, she never viewed her gender as an obstacle. I once heard her remark, after dealing with a difficult male legal giant over a CLE matter, ‘the cock may crow, but it’s the hen who lays the eggs.’”[58] She also served on the Board of Directors for the Law School Foundation and the Board of Trustees of the Farrah Law Society.

One of the most beloved professors at the law school has been Pam Bucy Pierson. The daughter of a Presbyterian minister, she moved from one small town in Texas to the next.[59] Professor Bucy’s interest in the law came early after one of her teachers commented to the inquisitive fourth grade student, “Pam, you ask so many questions, you ought to be a lawyer.”[60] She attended Austin College in Sherman, Texas and received her law degree from Washington University School of Law in St. Louis in 1978. At the time, approximately 20 percent of the nation’s law school classes were women. In contrast, her law class at Washington University had almost 50 percent.[61]

During her second year of law school, she was at the top of the class and interviewed with large law firms – not one made her an offer. Instead, she clerked for a judge on the Missouri Court of Appeals that summer. When that judge was named to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals, Professor Bucy clerked for him after law school graduation.[62] Following a short stint at a large law firm after her clerkship, Professor Pierson joined the Eastern District of Missouri’s U.S. Attorney’s office where she served as an Assistant U.S. Attorney from 1980-1987 in the criminal division specializing in white collar criminal fraud. She tried her first case within the first month as a prosecutor.

She and her husband stayed in St. Louis for eight years before he accepted a job in Alabama. Reluctantly, Professor Pierson left the “best job ever,” serving as a federal prosecutor, when her husband accepted a job in Alabama. She is quick to add that she is delighted she ended up in Alabama.[63] She loves the lesson that “all of the things we plan don’t work but the ones we don’t plan turn out to be great.”[64]

With the move to Alabama, she hoped to transfer to the U.S. Attorney’s office in Birmingham but there was a hiring freeze.[65] A law professor from Washington University encouraged her to reach out to law schools in the state. She did and when she joined the University’s law school, she and Camille Cook were the only two women present, as Martha Morgan was on leave. She taught criminal law, criminal procedure and white collar crime.[66] After a year at the law school, she received a call from the U.S. Attorney’s office informing her that the hiring freeze had ended. She turned them down and stayed because of her devotion to the students.[67] In particular, she enjoyed seeing them understand the concepts. She authored treatises on health care fraud and white collar crime.[68] During the Whitewater Scandal, she was often quoted by The New York Times about Ken Starr’s investigations.[69] She continues to be a legal scholar; she also spends time as of counsel to a firm with some of her former students and her son.[70] She has been delighted to serve on a non-profit that helps individuals re-enter society after serving in prison.[71]

We celebrate the “firsts” as well we should. For example, we should celebrate women like Sue Bell Cobb who was the first woman elected to serve as Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. Yet, we should also celebrate the many who passed through the doors of Farrah Hall and the later law school campus who contributed to the profession, their communities, and their families. Women like Mabel Yerby Lawson who graduated in 1920 and practiced in Greensboro with her father until 1925 or Eleanor O. Oakley who graduated from law school in 1931, married a fellow classmate (Lawrence Thomas) and moved to Dothan where they opened an office together. She left after two years to raise their two kids and then returned to practice in 1965. In 1966, she became a U.S. Magistrate judge. She served as a past president of the Houston County Bar Association, and it is believed she was one of the oldest practicing attorneys in the state.[72] With the firsts, seconds and thirds who paved the way for generations of women to come, the future of the profession can only continue to be bright. We celebrate these women and their accomplishments within the legal community and outside of it.

[1] The University of Alabama admitted two women in 1893. Anna Byrne Adams earned her degree in 1895, and Bessie Jemison Parker graduated the following year in 1896. See, Thomas Waverly Palmer, A Register of the Officers and Students of the University of Alabama, 1831-1901 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 1901), 370, 380.

[2] See David Krajicek, The Alabama Bench and Bar Historical Society Newsletter, Mar./April 2010,

[3] See id. (citing Maud McLure Kelly: Alabama’s First Woman Lawyer, Cynthia Newman, 1984 Samford University Research Series, paper no. 6).

[4] See id.

[5] See id.

[6]Ellen Turner, Trailblazers and Hearthkeepers: Female Law Students at the University of Alabama Before 1960, p. 5. See vertical file holdings, Special Collections, Bounds Law Library.

[7]“Women in Law in Alabama,” Elizabeth Johnson Wilbanks, The Ala. Lawyer, vol. 12 (1951), pp. 43-46. (E. Johnson, S.M. Hammond)

[8] The Washington Post, B 4, Wednesday, April 16, 1997. [Note great framed composite in box 1 MSS.0050]

[9] See Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Oral History Project, Nina Miglionico interview, dated Sept. 26, 2003, Tape 1.

[10] See Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Oral History Project, Nina Miglionico interview, dated Sept. 26, 2003, Tape 1.

[11] See Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Oral History Project, Nina Miglionico interview, dated Sept. 26, 2003, Tape 1. When Nina’s father asked his banker for a loan to pay for the law school tuition, the banker refused. When asked to explain his denial, the banker retorted Mr. Miglionico was wasting his money because his daughter would get married and never use her degree. In response, Mr. Miglionico said, “Well, if I give her an education nobody can take it away from her. But I leave her money, somebody can take it.” A family friend who was a lawyer secured a loan for the tuition. See id.

[12]See Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Oral History Project, Nina Miglionico interview, dated Sept. 26, 2003, Tape 1.

[13] Why No Women on Juries? Not Recognized as ‘People’, Birmingham Post-Herald, July 21, 1952; Martha Alexander, Federated Clubs Intensify Drive for Jury Service, The Birmingham News, Mar. 2, 1956.

[14] Nina Miglionico New Woman of the Year, named by BPW, The Birmingham News, Oct. 12, 1963.

[15] Ivan Swift, Bar Advocates Mayor, Council, The Birmingham News, Feb. 25, 1962, p. 116.

[16]Editorial, Council Choice is Important, The Birmingham News, March 5, 1963; see also April 2 Runoff Will Decide New City Government, Birmingham Post Herald, Mar. 7, 1963.

[17] See Letter from National States’ Rights Party, Dr. Edward R. Fields, Information Director, dated January 4, 1965.

[18] Emmett Weaver, Bryan and Wiggins Lead Vote for 9 Councilmen, Birmingham Post Herald, April 3, 1963.

[19] See Regular Minutes of the Council of the City of Birmingham, May 21, 1963 at 10:00 a.m. CST; Hollins Appointed to Planning Group, The Birmingham News, December 29, 1964.

[20] See Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Oral History Project, Nina Miglionico interview, dated Sept. 26, 2003, Tape 2.

[21] Mike Williams, Miss Miglionico to Pass Up Race for Council Seat, Sept. 12, 1985, The Birmingham News, 1A.

[22] Kitty Frieden, Cunning Miss Nina Wields Might but Fair Gavel, The Birmingham News, Apr. 6, 1980.

[23] Elizabeth Johnson Wilbanks, Women in Law in Alabama, 12 The Ala. Lawyer, 43, 43-46 (1951).

[24] Capstone Lawyer, pp. 26-27 (2022).

[25] Elizabeth Johnson Wilbanks, Women in Law in Alabama, 12 The Ala. Lawyer, 43, 43-46 (1951).

[26] Ellen Turner, Trailblazers and Hearthkeepers: Female Law Students at the University of Alabama Before 1960.

[27] See id.

[28] White v. Cook, 251 F. Supp. 401, 409 (M.D. Ala. 1966). Cf. Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975)(holding unconstitutional exclusion of women for jury service).

[29] Janie Shores, Just Call Me Janie, 9, (Anne Kent Rush ed., 1st ed. 2016).

[30] Id. at 17.

[31] Id. at 20.

[32] Id. at 39.

[33] Id. at 39.

[34] Id. at 39.

[35] Id. at pp. 44-45.

[36] Id. at 72.

[37] Id. at 45-46.

[38] Id. at 56.

[39] Id. at 30.

[40] Id. at 42.

[41] Id. at 71.

[42] Ellen Turner, Trailblazers and Hearthkeepers: Female Law Students at the University of Alabama Before 1960.

[43] Janie Shores, Just Call Me Janie, 74 (Anne Kent Rush ed., 1st ed. 2016).

[44] Id. at 212.

[45] Jay Reeves, First Female Member of the Alabama Supreme Court Dies at 85, U.S. News.com, Jay Reeves, AP.

[46] The Bedeviled Advocate, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Sept. 22, 1987).

[47] Marjorie Knowles Obituary – Sandy Springs, GA (dignitymemorial.com)

[48] Tuscaloosa News, Monday April 14, 1986.

[49] Deborah Spielberg, Faculty Gripe Session Preceded Knowles’ Resignation, Fulton County Daily Report, Nov. 2, 1990, p.2.

[50] Marjorie Fine Knowles, trailblazing lawyer, dies at 82 (ajc.com) (last visited July 9, 2023).

[51] Litera Scripta Obituary, October 2021; Email from Dean Mark Brandon to author, October 4, 2021. The increase in women’s enrollment during one three-year period, according to Dean Knowles’ obituary, was from 13 to 70.

[52] Alabama Alumni Magazine, June-July 1996, p. 26. Vol. 76, No. 4.

[53] Alumni Newsletter, UAL, Vol. 2, No. 1, Nov. 1983.

[54] Catalog (?), Faculty/Staff News, Vol. 10, No. 14 (10/8/90).

[55] Alog/Faculty/Staff.

[56] Camille Wright Cook | University of Alabama School of Law (ua.edu) (last visited July 9, 2023).

[57] ALR, Vol. 44, no. 3 (Spring 1993), “A Tribute to Professor Camille Wright Cook,” Nathaniel Hansford, p. 649 at 652.

[58] Al Lawyer.

[59] See Interview with Pam Pierson, dated Feb. 10, 2023.

[60] See id.

[61] See id.

[62] See id.

[63] See id.

[64] See id.

[65] See id.

[66] See id.

[67] See id.

[68] Bucy, WHITE COLLAR CRIME,CASES AND MATERIALS (West 3d ed. 2004; 2d ed. 1998; 1st ed. 1992); Supplements (1994, 2000); Teacher’s Manual (1992, 1998, 2004); Bucy, FEDERAL CRIMINAL LAW AND RELATED CIVIL CAUSES OF ACTION (with Beale and Welling) (West 1998); Supplements (1999, 2000); Bucy, HEALTH CARE FRAUD: CRIMINAL, CIVIL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW (Law 5 Journal Seminars Press 1996) (semi-annual updates) (In 1998, joined by three authors: Robert Fabrikant, Paul Kalb and Mark Hopson, and book retitled, HEALTH CARE FRAUD, ENFORCEMENT AND COMPLIANCE).

[69] Neil A. Lewis, For Starr and Hubbell, An Accord of Sorts, New York Times, July 1, 1999, A14; Neil A. Lewis, Managers’ Airtight Case against President Developed a Flat, New York Times, February 14, 1999, 27.

[70] See Interview with Pam Pierson, dated Feb. 10, 2023.

[71] See id.

[72] “Trailblazers and Hearthkeepers: Female Law Students at the University of Alabama Before 1960,” Ellen Turner.

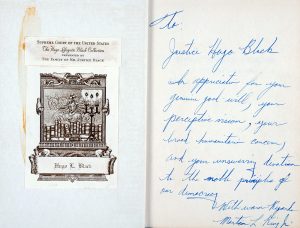

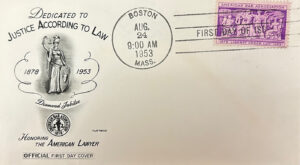

Usually, a ceremony is held to dedicate the new stamp. The stamp then goes on general nationwide sale the following day. Many prominent stamp dealers and first-day cover servicers have special commemorative illustrations and captions printed on the envelopes. These commemorative illustrations are known as cachets.

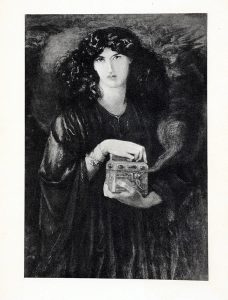

Usually, a ceremony is held to dedicate the new stamp. The stamp then goes on general nationwide sale the following day. Many prominent stamp dealers and first-day cover servicers have special commemorative illustrations and captions printed on the envelopes. These commemorative illustrations are known as cachets. The stamp depicts part of the frieze on the walls of the U.S. Supreme Court, which depicts four figures: Wisdom, Justice, Divine Inspiration, and Truth. The cachet depicts Lady Justice with her scales and shield.

The stamp depicts part of the frieze on the walls of the U.S. Supreme Court, which depicts four figures: Wisdom, Justice, Divine Inspiration, and Truth. The cachet depicts Lady Justice with her scales and shield.

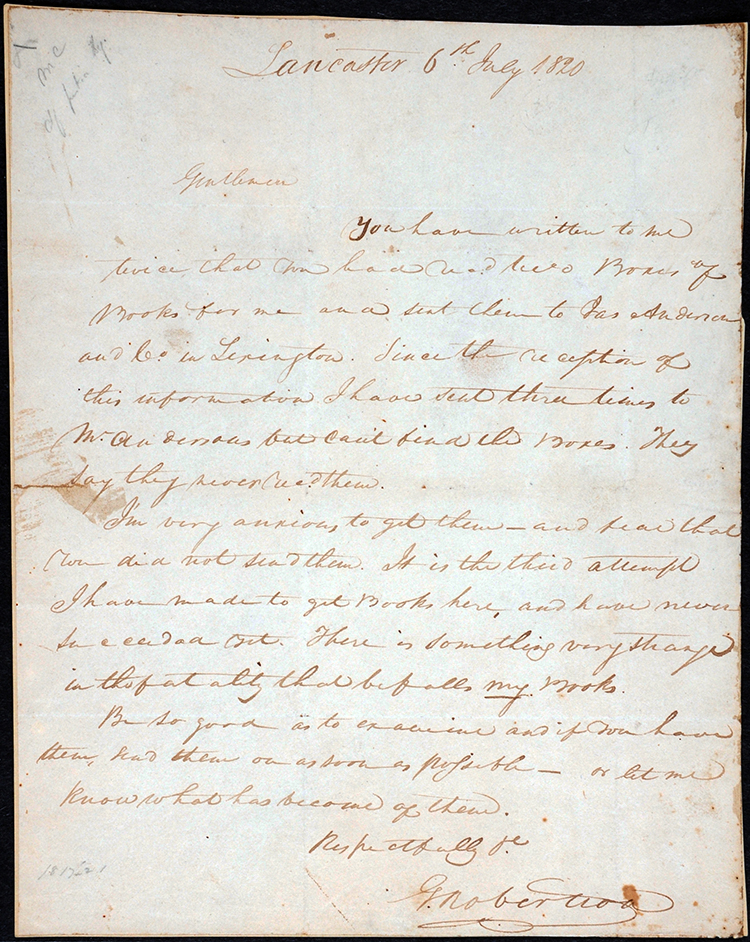

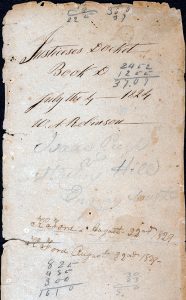

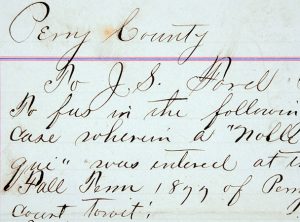

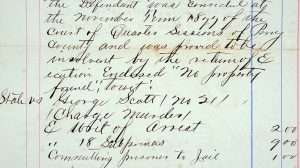

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.”

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.”