George Robertson and Book Consumers in Early 19th Century Kentucky

- October 16th, 2017

- by specialcollections

- in Collections, Guest Contributors, Recent Acquisitions

The following is a post by our friend Kurt X. Metzmeier containing commentary on a letter from our collection.

George Robertson and Book Consumers in Early 19th Century Kentucky

by Kurt X. Metzmeier

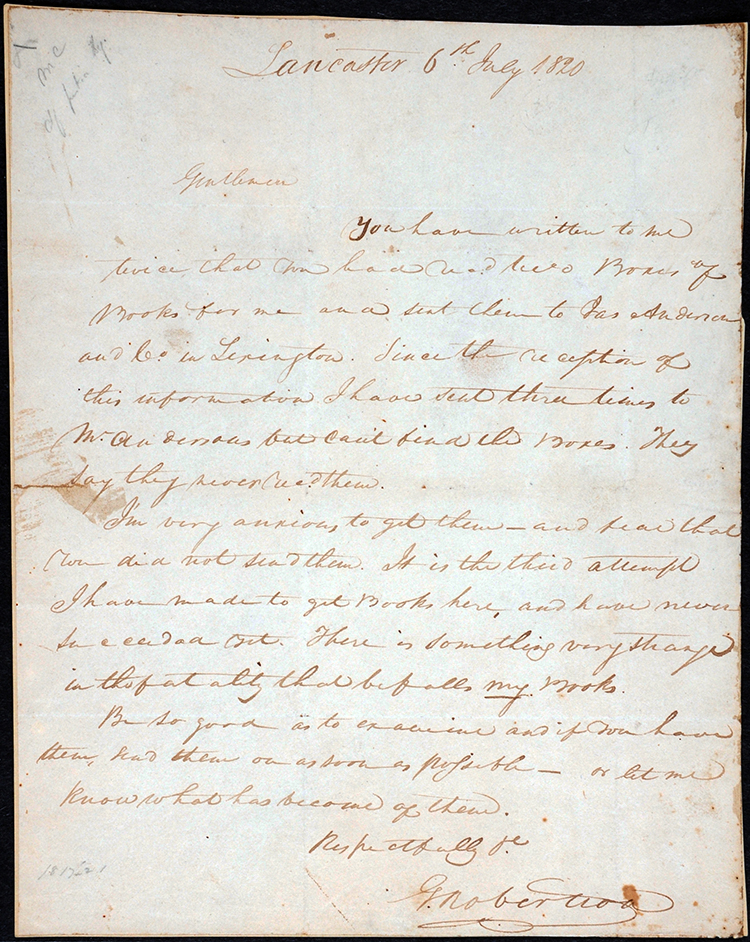

In an interesting 1820 letter, Kentucky lawyer George Robertson illustrates some of the difficulties of a book consumer on the expanding American frontier:

Lancaster 6th July 1820

Gentlemen,

You have written to me twice that you had rec’d two boxes of books for me and sent them to Jas Anderson and Co. in Lexington. Since the reception of this information I have sent three times to Mr. Anderson but can’t find the boxes. They say they never rec’d them.

I’m very anxious to get them—and fear that you did not send them. It is the third attempt I have made to get books here and have never succeeded yet. There is something very strange in the fatality that befalls my books.

Be so good as to examine and if you have them, send them on as soon as possible—or let me know what has become of them.

Respectfully &c

G. Robertson

The letter is a nice find. It involves one of the towering figures in Kentucky legal history at an early point in his life. It also shines a light into the book trade on the American frontier and does so in the middle of an economic crisis. Finally, the tone of the letter is relatively mild but you can faintly discern the rumblings of a legendary temper, one that would lead to one of the more famous fits of pique in Civil War history, a stubborn conflict that would involve governors, state and federal courts, and President Lincoln’s own wallet.

George Robertson (1790-1874)

George Robertson, whose portrait hangs in the courtroom of the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, served on Kentucky’s highest court 1829 to 1834, when he resigned to resume his private practice. He returned to the court to serve from 1864 to1871.[1] For a quarter-century, he led the prestigious law department at Transylvania University, teaching men like John Marshall Harlan the rudiments of jurisprudence.[2] His decisions on issues of criminal law and tort law were widely cited, and Kentucky histories and bar tributes mark him as a leading figure in the pantheon of state judges.[3]

However, in 1820 this was all in the future. Robertson was at this time a journeyman lawyer (he had been practicing law since he turned 19-years-old) and a U.S. Congressman serving his third term. He had just completed a term as chair of the public lands committee and, in the prior year, had successfully sponsored a bill which he wrote to establish the territorial government of Arkansas.[4] However, being “poor and having a growing family,” he would soon quit his seat to concentrate on the practice of law.[5] Perhaps the two boxes of books he purchased were the working law library he needed to establish his new law office.

The Kentucky Book Market in 1820

From his home in the Bluegrass, Robertson would have had many opportunities to assemble a well-balanced library and legal collection.[6] Nearby Lexington was the intellectual capital of Kentucky for its first half century. As noted by pioneer William A. Leavy (whose 1873 manuscript memoir depicts a commercial life in pioneer Lexington), in 1820 it already had several booksellers.[7] Most had long associations with the publishing centers in Philadelphia and Cincinnati.[8]

As the letter suggests, many Kentuckians also purchased books by post. In “Nursery of a Supreme Court Justice,” Peter Scott Campbell and I examined probate records of books in the library of Robertson’s neighbor from nearby Danville, James Harlan.[9] We found Harlan owned many titles from the “Law Library.” Set up like the old Book-of-the Month Club, the Law Library was published by Philadelphia firm of T. & J.W. Johnson, which reprinted English legal treatises and mailed them out regularly to subscribers.

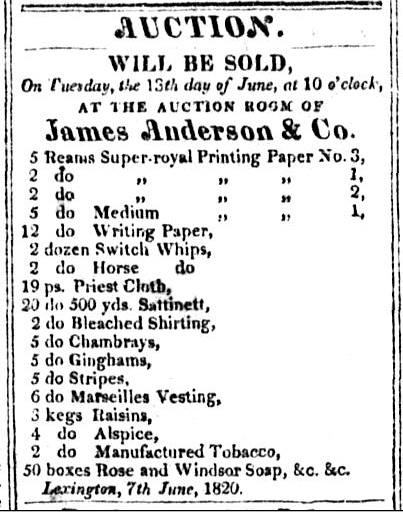

Books could also be bought from merchants like the Anderson family, a mercantile clan whose patriarch George established a general store in Lexington in 1788. Leavy notes that “Anderson’s place of business and residence” was a “2-story stone building” on the corner of Main Street and Cheapside” in the heart of Lexington. He was “succeeded in business by his sons, Thomas and James, who were successful in their business.”

James, who years later would have a “very successful career as auction and commission merchant,” is likely the planned recipient of Robertson’s lost books. Lexington stores like Anderson & Co. would often allow themselves to be the mailbox recipient for large packages sent to rural consumers. This relationship was firmly based on mutual trust. All in all, it is unlikely that Anderson was to blame for Robertson’s lost library.

The date of July 1820 may shed some light on what might have happened to Robertson’s books. In January 1819, the cotton market dropped 25% in what economists would later see as the first sign of the great depression known to historians as the Panic of 1819. The slow economic recovery of Europe from the Napoleonic Wars led to a global monetary crisis. The Bank of the United States would respond by calling in debts and seeking to return gold specie back to its vaults in Philadelphia. In the Western country, this led to similar tightening of credit by state and independent banks. Businesses collapsed, farms went under, and the ready cash necessary for commerce was lacking. Frontier states like Kentucky and Ohio were hit hard by the crisis.[10] It is very possible that Robertson’s unnamed bookseller was scrambling to avoid bankruptcy, putting off his customers with white lies while hoping for a loan to set things right.

An Angry Old Man in a Hurry?

If Robertson held his temper over his lost books, he did not do so in an incident during the Civil War that placed a stubborn Judge Robertson up against the 22nd Wisconsin and its equally headstrong commander—a conflict so politically sensitive that it ended up on the desk of Abraham Lincoln.

It all began in 1862 when a 19-year-old slave that Robertson owned (but leased to an “Irishman”) ran away and sought refuge among the Wisconsin troops then stationed in Lexington. Robertson had long opposed slavery in theory but had still owned a few slaves. This particular slave, Adam, had apparently suffered real abuse from the man Robertson had entrusted with his care.

Robertson was an old family friend of Abraham Lincoln and had been the Lincoln family’s lawyer when they needed assistance settling the estate of Mary’s father, Robert Todd.[11] When the judge published a book of essays and speeches in 1855, Scrap Book of Law and Politics, he sent a copy to his Illinois friend. Lincoln thanked him in a famous August 15, 1855 letter that foreshadowed his 1858 “House Divided” speech. Noting that one of Robertson’s essays opposed slavery, Lincoln expressed his worry that the despised institution might break up the Union: “Can we, as a nation, continue together permanently—forever—half slave and half free?”[12]

In 1861, Robertson had enthusiastically declared as a Unionist; but as the war had progressed, it became necessary to station more U.S. troops in Kentucky and the Northern-raised troops tended to clash with the locals. When he arrived at the camp of the 22nd Wisconsin, Robertson asked for the return of his slave but was smartly rebuffed by Col. William T. Utley. As related later by Utley’s friend and the unit’s chaplain, George S. Bradley, Robertson declared he was a citizen of a loyal state and Utley had no right to confiscate his property. He explained that he “never liked slavery” and was the “only man living who had voted for the Missouri Compromise” but, as a loyal Kentucky Unionist, his property could not be legally confiscated. Utley responded that he “had never had much confidence in the loyalty of Kentucky” and that he didn’t think himself subject to the laws of Kentucky.[13]

According to Leach, Robertson “drove out of camp in high dudgeon.”[14] He promptly had Utley indicted in Jessamine County Circuit Court on a charge of slave-stealing, a crime that could result in up to 20 years imprisonment.[15] As Utley acknowledged in a Nov. 17, 1862, letter to Wisconsin Gov. Alexander Randall, “All of Kentucky is ablaze” and Utley personally was “in a devil of a scrape.”[16] Utley then wrote President Lincoln. Lincoln sized up the knotty politics of the conflict and responded by writing Robertson on Nov. 26, offering to pay him $500 out of Lincoln’s own pocket to make the controversy go away.[17] By now Robertson was beyond reasoning with, and he wrote Lincoln back to say it was a matter of principle: “[M]y object in that suit was far from mercenary—it was solely to try the question whether the civil or the military power is Constitutionally supreme in Kentucky.”[18]

While Utley and the Wisconsin 22d decamped to Tennessee, Robertson rode his indignation back into the Court of Appeals in an 1864 election campaign based on anger against the Union troops in the state.[19] He would eventually win his lawsuit and successfully enforce the $935 judgment against the federal government in 1871–well after the purported principle was mooted by the end of the war.[20]

At his death in 1874, Robertson was lauded as one of the state’s greatest citizens. But as new generations assess the horrors of slavery more critically, this incident continues to tarnish his reputation. It is hard to take one’s record of opposition to slavery seriously if you end your career angrily suing people over the loss of a much-abused young slave.

History has not recorded what happened to Robertson’s two boxes of missing books in 1820. Perhaps he wrote them off as a loss to the turbulent times. That certainly would have been Robertson’s wisest course in 1862.

Kurt Metzmeier is associate law librarian at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law. He is the author of Writing the Legal Record: Law Reporters in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky (University Press of Kentucky, 2016).

[1] The biographical literature on Robertson is extensive. George Robertson wrote two books with significant biographical material, Scrap Book of Law and Politics (Lexington, n.p., 1855) and Outline of the Life of George Robertson: Written by Himself (Lexington: Transylvania Printing & Publishing Company,1876) and there are entries on the judges in major state encyclopedias. Robert M. Ireland, “George Robertson” in Kentucky Encyclopedia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993):776 and H. Levin, ed., Lawyers and Lawmakers of Kentucky (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1897): 71.

[2] Both as a student and later as a judge himself, Harlan idolized Robertson. If Robertson had been placed on the U.S. Supreme Court, he later wrote, he would have “left a royal heritage as jurist of our nation.” See Loren P. Beth, John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992):17-18.

[3] Robert M. Ireland’s entry in the Kentucky Encyclopedia reflects a century-worth of consensus in Kentucky. Peter Karsten in Heart Versus Head Judge-Made Law in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1997) highlights Robertson’s impact on Southern jurisprudence.

[4] 3 Stat. 493 (March 2, 1819).

[5] Robertson, Outline, 56.

[6] The rise of Kentucky book culture is well-documented. The spread of literacy, book publishing, and libraries are surveyed in William Henry Venable, Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley, Historical and Biographical Sketches (New York: P. Smith, 1949) and in Howard H. Peckham, “Books and Reading on the Ohio Valley Frontier,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 44 (1958),649-63. Kentucky’s own pioneer publishing industry was well-established by the 1820s. See William Henry Perrin The Pioneer Press of Kentucky ( Louisville: John P. Morton & Co, 1888) , Willard Rouse Jillson, The First Printing in Kentucky; Some Account of Thomas Parvin and John Bradford and the Establishment of the Kentucky Gazette (Louisville: Dearing Printing Co., 1936). and Douglas C. McMurtrie, John Bradford, Pioneer Printer of Kentucky (Springfield, Ill: n.p., 1931).

[7] William A. Leavy, “A Memoir of Lexington and Its Vicinity,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 40 (1942): 107-31, 253-67, 353-75; 41, (1943): 44-62, 107-37, 250-60, 310-46; (1944): 26-53.

[8] See Walter Sutton, The Western Book Trade Cincinnati As a Nineteenth-Century Publishing and Book-Trade Center (Columbus: Ohio State University Press for the Ohio Historical Society, 1961).

[9] “Nursery of a Supreme Court Justice: The Library of James Harlan of Kentucky, Father of John Marshall Harlan,” Law Library Journal 100 (2008):639-74.

[10] These economic dislocations ravaged Kentucky commercial life in the 1820s. Politicians who wanted the state to forgive crushing debts on citizens even replaced the state’s high court when it struck down relief laws, leading to “court controversy” in 1824-25 when Kentucky had two rival appellate courts. See Kurt X. Metzmeier, Writing the Legal Record: Law Reporters in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017).

[11] Lincoln had practiced law in Kentucky courts alongside Robertson, who also was a neighbor and friend of Mary Todd’s family in Lexington. See especially William H. Townsend, Lincoln and the Bluegrass: Slavery and Civil War in Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1955) and Lowell H. Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000).

[12] Lincoln to Robertson, Aug. 15, 1885, quoted in Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, 92. In a June 16, 1858, speech accepting his nomination in Springfield as the Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, Lincoln discussed the conflict over slavery: “In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.” See Mario M. Cuomo, ed. Lincoln on Democracy (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), 105-114, 105.

[13] Townsend, 299-304), and Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, 233-35, relate the story from Kentucky sources. George S. Bradley, The Star Corps: or, Notes of an Army Chaplain (Milwaukee: Jermain & Brightman,1865), 63-79, and E.W. Leach, Racine County Militant; An Illustrated Narrative of War Times (Racine, WI: Leach, 1915), 97-106, provide the Wisconsin prospective.

[14] Leach, Racine County Militant, 100.

[15] Rev. Stat. of Ky., ch. 93, art. 5, sec. 1-5 (1852).

[16] Utley to Randall, Nov. 17, 1862, quoted in Townsend, Lincoln and the Bluegrass, 303-04.

[17] Lincoln to Robertson, Nov. 26, 1862, quoted in Townsend, Lincoln and the Bluegrass, 302.

[18] Robertson to Lincoln, Dec. 1, 1862, quoted in Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, 235.

[19] Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, 190-91.

[20] Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, 235.