The following is the first of several posts that will explore selected titles from a collection of law and law-related books donated by the family of A.S. Williams, III. The Williams Historic Law Book Collection consists of seventy volumes that date from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. They are in their original bindings, and many of them have penciled notes on the margins and flyleaves.

These lovely books were donated to the Bounds Law Library by the family of Birmingham insurance executive and noted bibliophile A.S. Williams, III. Williams’ magnificent collection of more than “20,000 volumes and pamphlets published between the late-seventeenth century and 2009” is a major holding of the Hoole Special Collections Library.[1] The family’s gift to the Bounds Law Library consists, as noted above, of a legal collection assembled by Williams’ father-in-law, the late G.G.W. Hoover. Hoover was himself an insurance executive and a man who had a rare appreciation of the printed sources of the common law.[2] A few titles from this collection are briefly described below, in alphabetical order by author.

James Barr Ames, A Selection of Cases on Pleading at Common Law (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson & Son, 1875). This is one of the first “casebooks” produced at Harvard during the deanship of Christopher Columbus Langdell. Ames (1846-1910) was one Harvard’s leading professors.[3] The theory behind the “casebook method” was that students, by reading properly arranged cases, would be able to deduce the principles and rules of law for themselves. Since the late 19th century—indeed, today—the casebook method has prevailed in American law schools. This copy of Ames contains numerous (and voluminous) marginal notes in a late 19th-century hand.

Charles W. Bacon, et al., The American Plan of Government, 4th edition (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921). Bacon (1856-1938)[4] was a New York lawyer and an instructor in Political Science at the City College of New York.[5] He authored several works on the U.S. Constitution.

This volume contains notes on the front pastedown leaf and front free flyleaf, as well as underlining and other annotations in the text. These are in the hand of the book’s early owner William H. Wilson. One of Wilson’s flyleaf notes tells us that the book was purchased on February 6, 1952, at Claitor’s Book Store in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Claitor’s is a longstanding bookstore, publishing house, and landmark of Louisiana’s world of books. Several of the titles in Bounds’ Williams Collection bear Claitor’s distinctive blue and white sticker.

James M. Beck (1861-1936) was a Philadelphia native and distinguished practitioner of law, admitted over the course of his career to the bars of Pennsylvania, New York, and England (he was made a bencher of Gray’s Inn in 1914). During World War I, Beck wrote articles and gave addresses against German aggression. In the 1920s he served as Solicitor General (1921-1925), appointed by President Warren G. Harding. Then he was elected to Congress as a Republican from Pennsylvania, serving from 1927 until his resignation in 1934. Beck resigned because he considered that Congress had become a “rubber stamp” for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Beck was a leading political conservative, whose books reflected his concern for the rights of the states.[6]

The A.S. Williams collection at Bounds includes three titles by James M. Beck, as follows:

(1) The Constitution of the United States: Yesterday, Today—and Tomorrow? Foreword by President Calvin Coolidge (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1924). Beck’s Wikipedia article says of this title that “It was a best-seller, going through seven printings within ten months. A special edition of 10,000 copies, with a foreword by President-elect Coolidge, went to schools and libraries across the country.” This copy contains many handwritten notes (mostly in pencil) on the recto of the front free flyleaf and at various points in the margins of the text.

(2) May It Please the Court, O.R. McGuire, editor (New York: Macmillan, 1930). This title consists of a number of speeches, articles, and addresses, some historical and some political. With the exception of a penciled date of the recto of the front free flyleaf, it appears to be unmarked.

(3) Our Wonderland Of Bureaucracy (New York: Macmillan, 1932). This critique of the complexities of modern government (published just before the advent of the New Deal) contains a good deal of heated language. On socialist leaders (p. 85), Beck says that their message appeals “particularly to the lower intelligence, which fears its own capacity and sub-consciously favors a dictatorship.” A slim notepad laid in the book contains several brief notes, including a quote from Aristotle: “The laws have no lasting vitality save in the spirit of the people.”[7]

Louis B. Boudin (1874-1952), Government by Judiciary, 2 volumes (New York: William Godwin, Inc., 1932). Boudin was a member of a group that was surely underrepresented in this collection. His Wikipedia page describes him as “a Russian-born American Marxist theoretician, writer, politician, and lawyer,” and says that he is chiefly remembered for Government by Judiciary. This work counters the views of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Specifically, Boudin takes Holmes to task for agreeing with Chief Justice Marshall that the U.S. Supreme Court has the power to declare laws unconstitutional. The work’s annotator (who favored red pencil) was likewise critical of this doctrine. He wrote “No! No!” opposite a passage setting forth Marshall’s view of the matter. This volume shows that legal populism was alive in Alabama, or wherever the annotator happened to live.

These volumes contain a number of marginal notes in red pencil. In many instances, the annotator was quite critical of Boudin’s interpretations. At the top of page 25, he asks: “How could [his] implication make both legislature and Supreme Court both supreme!!” On page 169, the annotator responds to the notion that Federalism or Antifederalism was “a matter of geography” by saying tersely: “No, never was.”

By the time he got to Chapter 33, on “Due Process of Law and Trial by Jury,” the annotator was taking marginal notes in a nearly auto-written mode. In the margin of page 357 he writes: “Trial by jury a good thing.” A few pages on, he summarizes what he has just read with the comment: “All silly.” On page 361, when Boudin refers to grand jury deliberations as “part of trial by jury,” the annotator comments: “But not an essential part.” On page 363, in response to another passage discussing juries, he writes: “But are not rights preserved as well by a jury of 8 as by 12?” Two pages later he attacks again, then relents: “What! Yet maybe so.”

Henrici de Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae, edited by Sir Travers Twiss, 6 Volumes (London: Longman & Co., 1878). Volume I contains an Introduction, pp. [ix]-lxvi, and a detailed “Index,” pp. lxxvii-cv. Similar detailed indexes head up the main text in each of the six volumes. The main text is presented throughout the work in Latin and English on facing pages. A more conventional index is presented after the main text in each of the volumes.

Each volume contains the bookplate of Seneca Haselton (1848-1921), a notable lawyer, mayor of Burlington in Vermont, Minister Plenipotentiary to Venezuela (1894-1895), and member at different times of the Vermont State Supreme Court.[8]

Henrici de Bracton[9] (c. 1210-1268) was a Devonshire man who served as clerk to the great royal judge William of Raleigh, Henry III’s trusted advisor and Chief Justice. By most modern accounts, the treatise known as “Bracton” was compiled in the 1220s or 1230s by Raleigh and passed along to Bracton, who put it in its final form. Bracton was a learned man in his own right, having studied Civil Law at Oxford. Indeed, the treatise De Legibus is remarkable for its efforts to reconcile common law and the ius commune, including Roman and canon law. It is equally notable for its use of case notes (of over 400 cases) to illustrate points of pleading and doctrine. It was the first English treatise to do so. The great medieval historian Frederic William Maitland discovered Bracton’s “Notebook.” This was a personal reference work containing notes of some 2,000 cases. Maitland published an edited edition of it in 1887.[10]

De Legibus opens with a much-quoted passage on the needs of a king:

“These two things are necessary for a king who rules rightly, arms forsooth and laws, by which either time of war or of peace may be rightly governed, for each of them requires the aid of the other, in order that on the one hand the armed power may be in security, and on the other the laws themselves may be maintained by the use and protection of arms.” [I: 2][11]

Maitland called Bracton’s De Legibus “the crown and flower of English jurisprudence.”[12] Given the decades that it took to put this work together, the brilliant legal minds that worked on it, and the universal jurisprudence to which it aspired, the treatise has earned such praise.

Thus endeth the first installment concerning our A.S. Williams Collection titles. This selection has contained, among other things,

(1) An early casebook, one of the foundation-stones of twentieth-century legal education.

(2) Works by a prominent anti-New Deal lawyer.

(3) An important work by a notable “Marxist Theoretician.”

(4) A gleaming jewel of the Middle Ages.

What more could one ask for?

PMP

[1] For a description of Hoole’s A.S. Williams III Americana Collection, see the guide at https://guides.lib.ua.edu/williams-collection.

[2] Mr. Hoover died in 1976 at the age of 85. Mr. James Williams furnished Mr. Hoover’s obituary, dated June 9, 1976 (newspaper unknown).

[3] For Ames’ Wikipedia article, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Barr_Ames.

[4] For Bacon’s obituary, see New York Times, November 11, 1938.

[5] For a scathing review of this title, see 31 Political Science Quarterly 626-628 (Dec., 1916).

[6] For Beck’s Wikipedia article, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Barr_Ames.

[7] Our Wonderland of Bureaucracy, x.

[8] See Wikipedia, “Seneca Haselton,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Haselton.

[9] Sometimes spelled De Bratton.

[10] See in Bounds Law Library, at KD600 .B73 1887.

[11] The quote is even more sonorous in a more recent translation of Bracton. See George E. Woodbine, editor, On the Laws and Customs of England, Samuel Thorne translator, 4 volumes (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), thusly: “To rule well a king requires two things, arms and laws, that by them both times of war and of peace may rightly be ordered. For each stands in need of the other, that the achievement of arms be conserved [by the laws], the laws themselves “preserved by the support of arms.” The Woodbine/Thorne Bracton is available at the Bounds Law Library (Reserve) at KD660 .B7.

[12] See the Ames Foundation website, at https://amesfoundation.law.harvard.edu/digital/Bracton/bracton.html.

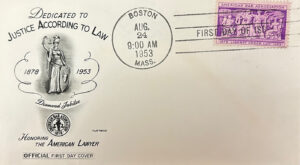

Usually, a ceremony is held to dedicate the new stamp. The stamp then goes on general nationwide sale the following day. Many prominent stamp dealers and first-day cover servicers have special commemorative illustrations and captions printed on the envelopes. These commemorative illustrations are known as cachets.

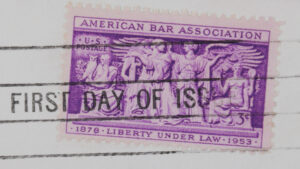

Usually, a ceremony is held to dedicate the new stamp. The stamp then goes on general nationwide sale the following day. Many prominent stamp dealers and first-day cover servicers have special commemorative illustrations and captions printed on the envelopes. These commemorative illustrations are known as cachets. The stamp depicts part of the frieze on the walls of the U.S. Supreme Court, which depicts four figures: Wisdom, Justice, Divine Inspiration, and Truth. The cachet depicts Lady Justice with her scales and shield.

The stamp depicts part of the frieze on the walls of the U.S. Supreme Court, which depicts four figures: Wisdom, Justice, Divine Inspiration, and Truth. The cachet depicts Lady Justice with her scales and shield.

Gary Aldridge was a 1978 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Law who died in a 1998 rafting accident in Alaska at age 47. His widow, Marsha White Aldridge said of Aldridge, “throughout his professional and public career Gary truly dedicated himself to making sure the law worked for everyone.”

Gary Aldridge was a 1978 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Law who died in a 1998 rafting accident in Alaska at age 47. His widow, Marsha White Aldridge said of Aldridge, “throughout his professional and public career Gary truly dedicated himself to making sure the law worked for everyone.”

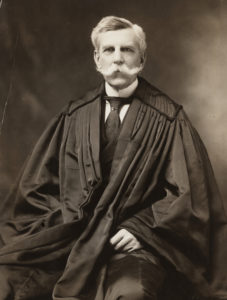

He served on the high court from 1902-1932, and secured renown as a defender of free speech; see his dissent in Abrams v. United States (250 U.S. 616, (1919). Holmes was likewise willing to allow states considerable leeway in their regulation of economic interests and public welfare.

He served on the high court from 1902-1932, and secured renown as a defender of free speech; see his dissent in Abrams v. United States (250 U.S. 616, (1919). Holmes was likewise willing to allow states considerable leeway in their regulation of economic interests and public welfare.

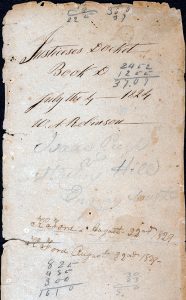

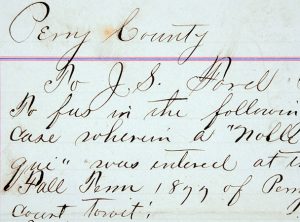

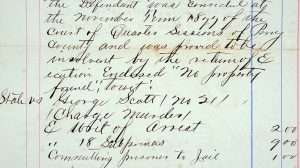

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.”

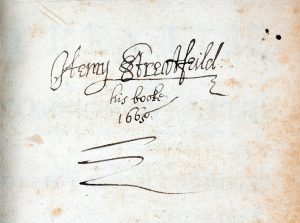

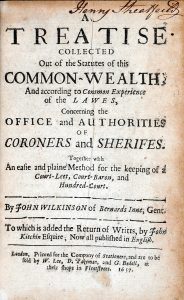

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.” By this time there had been no king on the throne since the execution of Charles I in 1649. Puritans and supporters of Oliver Cromwell’s “Protectorate” were very much in control of the nation. They expected sheriffs and other officials to enforce punitive laws based, more or less overtly, on Puritan notions of morality. Consider this passage, from page 174 of Wilkinson’s book:

By this time there had been no king on the throne since the execution of Charles I in 1649. Puritans and supporters of Oliver Cromwell’s “Protectorate” were very much in control of the nation. They expected sheriffs and other officials to enforce punitive laws based, more or less overtly, on Puritan notions of morality. Consider this passage, from page 174 of Wilkinson’s book: