Tour of an Unusual Book: The Black Spot

- January 30th, 2019

- by specialcollections

- in General, Preserved in Amber, Unique or Annotated Works

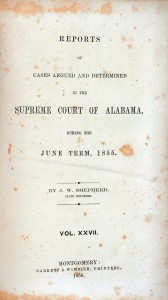

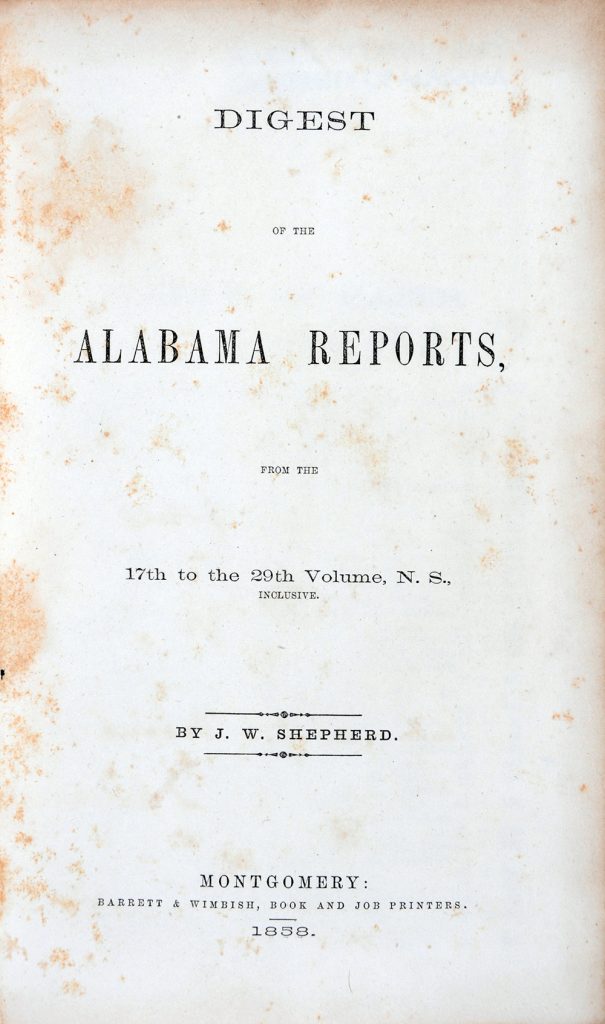

The Bounds Copy of J.W. Shepherd’s Digest of the Alabama Reports from the 17th to the 29th Volume, N.S. [New Series]. Montgomery: Barrett & Wimbush, Book and Job Printers, 1858.

Our “Preserved in Amber” series of posts seeks to celebrate unique and interesting objects, usually but not always a particular volume. The uniqueness typically comes from one striking feature—such as the correspondence between Hannis Taylor and J.B. Bury, pasted in Bounds’ copy of Taylor’s Science of Jurisprudence and featured in our October 12, 2016 post. To the law review spader or other casual user, there would be nothing particularly arresting about our Shepherd’s Digest. Further investigation, however, reveals a book that is interestingly signed and tantalizingly inscribed. Still more investigation reveals a mysterious blemish—quite unexpected. This latter, to be sure, was a feature that invoked this writer’s inner twelve-year-old, who arrived equipped with one of his favorite books.

First, the Book and Its Owners:

J.W. Shepherd, author of the Digest, was born in Madison County, Alabama, in 1826. He graduated from Yale College in 1844 and returned home to practice law. By 1851 he was practicing in Montgomery and was tapped as the reporter for the Alabama Supreme Court, a post he would fill (with various interruptions) until the early 1890s.[1] In line with regional publishing practices of the time, Shepherd published his 1858 Digest close to home, with Barrett & Wimbush of Montgomery.

The Bounds copy of the Digest is inscribed with three names on the front pastedown leaf. The first, written in red pencil, is that of R.W. Walker. This signature could well be that of Richard Wilde Walker, who in 1859 would be appointed to fill a vacancy on the Alabama Supreme Court. Walker would go on to serve in the Confederate Provisional Congress and (1863-1865) in the Confederate Senate.[2] In 1859, Walker sold the Digest to one Thomas Alan Jones, according to an inscription in Jones’ handwriting. At some point thereafter, Jones “presented” the Digest to James Irvine, quite likely the James Irvine who would represent Lauderdale County in the Alabama constitutional convention of 1865.[3]

Further Study:

The first indication that the Walker-Jones-Irvine Digest contains anything unusual can be found on the verso of the rear free flyleaf. There can be seen the remains of an inscription in pencil, almost wholly erased but beginning with the words “Preposterous Monstrosity” and ending with the words “to take it back.” It is written, apparently, in Walker’s hand; and its erasure probably represents nothing more than a courtesy from one owner to the next. Or was there something written that Walker or one of the book’s other owners didn’t want anyone to read? Unless we can stage a highly specific question-and-answer séance, we’ll probably never know.

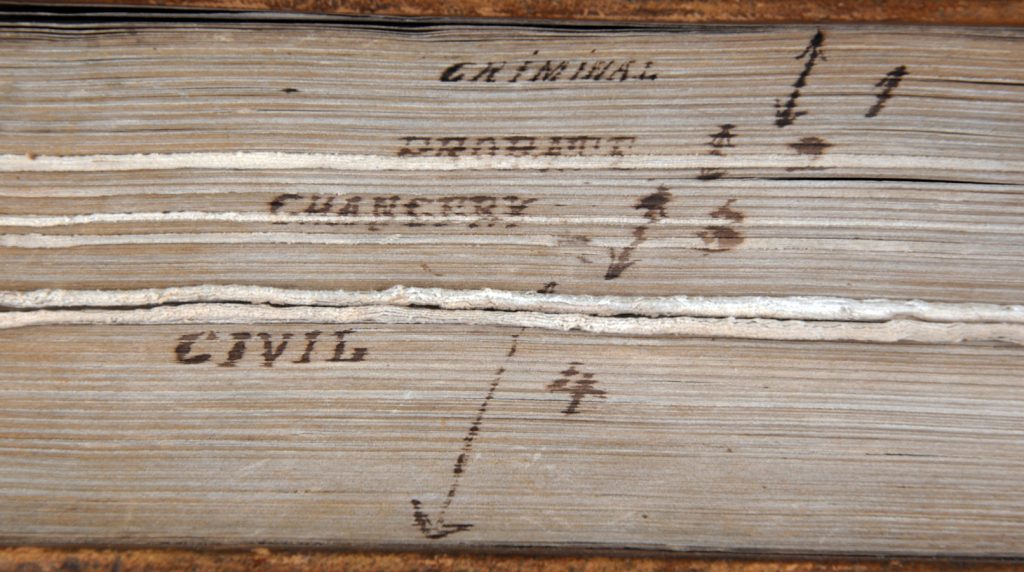

Moving toward an examination of the exterior text block, we see more proof that every printed book—mass-produced or otherwise—can become a unique object in the hands of its readers. Part of this Digest’s individuality is inked on the fore-edge of the text block in the form of a handy index. The categories are broad, certain to have been applicable to the practice of the period: Criminal, Probate, Chancery and Civil. Each of these words was accompanied by an arrow marking its extent in the text, and also by a number from 1 (opposite Criminal) to 4 (opposite Civil). The intent—purely practical—is far removed from that of fore-edge artists who have decorated books with symbolic, heraldic, or decorative images.[4]

Proceeding to the actual text of the Digest, we see that one reader (at least) has resorted to marking places with often rather emphatic dog-ears. These dog-ears are placed on or opposite to pages containing the following topics: Constitutional Law (p. 30); Court and Jury (p. 37); Pleading (p. 95); Statute of Limitations (p. 197); Assumpsit (p. 403); Evidence (pp. 626-627); and Execution (p. 630).Someone, in addition, drew (in ink) brackets around three sections of “The Trial of the Right of Property” (p. 761). Aside from these indications of research interests, there are few ordinary alterations to this copy of the Digest; but the dog-ears and marks suggest that its owners pursued the ordinary practice of law.

Interesting Possibilities:

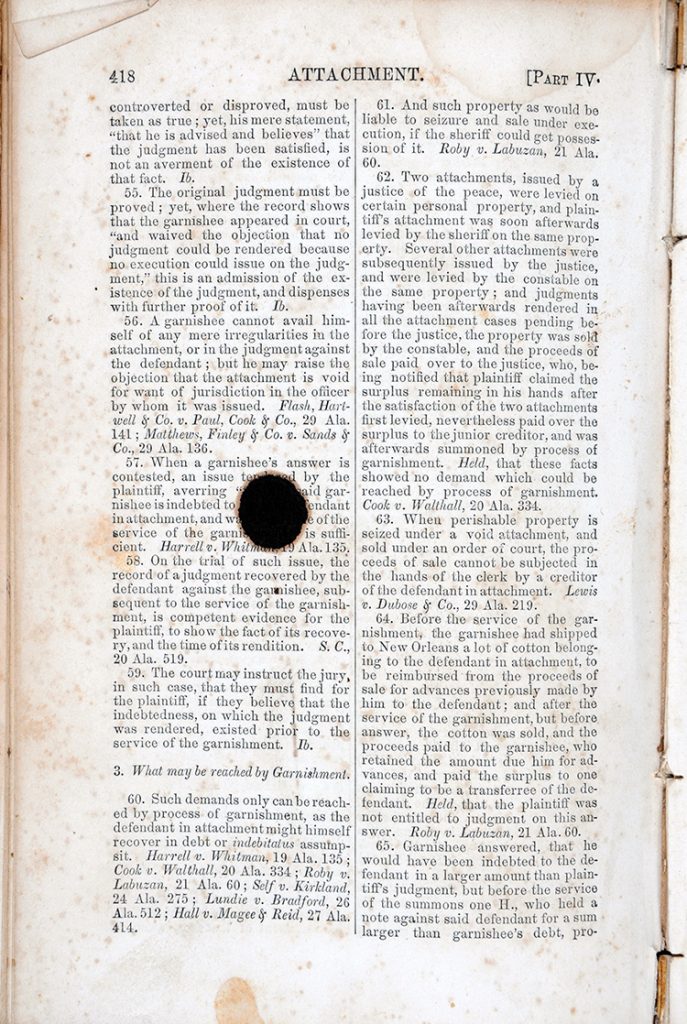

We encounter a much less ordinary set of marks beginning on p. 417. What presents itself, in the middle of §50 of the article on Attachment is a virtually circular mark 1.5 centimeters in diameter. It is a consistent dark brown in color; it has moved through the paper to produce an identical mark on p. 418. Each of these marks has stained its facing page (pp. 416, 419). The look of these dark marks suggests that they were burned—burned with considerable care, possibly by means of a fair-sized lit cigar.[5] For all the world, they look strangely familiar, like something that resonates in memory.

Of course! What we’re seeing is like a black spot in Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 classic Treasure Island. All at once the air seems full of references to lubbers and swabs—charged, too, with the likelihood that we’ll catch a glimpse of the fearsome one-legged seafaring man, Long John Silver. Just outside my office, surely, Billy Bones is explaining to young Jim Hawkins that the black spot is “a summons, mate,” issued by a pirate crew to someone they wished to depose or kill. I’m reminded of a scene late in Treasure Island, where Jim Hawkins watches the pirates preparing a black spot. They were clustering around a campfire; one was “on his knees in their midst.” Hawkins saw “the blade of an open knife shine in his hand with varying colors”; and “he had a book as well as a knife in his hand.”[6]

Melancholy Conclusions:

After a few days’ thought and very little (to be honest) further research, I am forced to admit that it is unlikely that our Digest ever fell into the hands of pirates, or even lawyers’ children pretending to be pirates.[7] For one thing, its spot[s] do not conform to the rules laid down in Treasure Island. Pirates of that book’s Caribbean cut their black spots out of books, leaving one side unscorched. The unscorched side was supposed to be blank, so the pirates could write on it some cryptic sentence of doom. The Walker-Jones-Irvine spot, on the contrary, is burned on both sides, and there is no evidence that anyone ever took a knife to the volume.

Moreover, the black spot made by firelight in Treasure Island (see above) still carried s few words of text—a spookily burned fragment of the Book of Revelations, namely: “Without are dogs and . . . murderers.” [8] The Bounds Digest also boasts darkened texts surrounding its double spot, but the texts are all about regulations for the attachment of property. One, for example, commences: “When a garnishee, against whom a judgm[ent has] been rendered by a justice [of the pea]ce, removes the case to the [unintelligible] [c]ourt . . .”[9] To be sure, this passage once provided a revealing look into legal maneuvers that preceded the carting away of one’s possessions; but it is a bit lacking in dramatic pep.

Finally, there are doubts concerning whether pirates ever used black spots at all.[10] Perhaps, after all, it is better to argue that the Digest’s black spot[s] were caused by the carelessness of a smoker, piratical or otherwise, who thought he was putting his cigar down into an ashtray.

PMP

[1] Thomas M. Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, introduction by Milo B. Howard, Jr. (1921; Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Company, 1978), IV: 1543-1544. Willis Brewer, in his Alabama: Her History, Resources, War Record, and Public Men from 1540 to 1872 (Montgomery: Barrett & Brown, 1872), 474-475, said that Shepherd was “a gentleman of a retiring disposition, but esteemed for many excellencies of head and heart.”

[2] Brewer, Alabama, Her History, 355-356.

[3] Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, III: 885.

[4] See Roy Stokes, A Bibliographical Companion (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1989), 117-118.

[5] An alternate theory is that the spots were formed by the application of ink. This seems less likely because the marks on pp. 417-418 are each enclosed by a little halo of what appears to be scorched paper. And ink, unless applied by a deft hand, would quite possibly not have been so neat.

[6] Robert Louis Stevenson, Treasure Island (1883; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press, 2013), 22, 238.

[7] The latter possibility is still open to speculation, of course.

[8] Revelation 22:13.

[9] Shepherd, Digest, 417 (§50).

[10] See Wikipedia article “Black Spot (Treasure Island).”