A New Day, a New Building: Albert J. Farrah’s Years of Victory

- March 10th, 2023

- by specialcollections

- in 150 Years of UA Law History, General

The following is a post which discusses the history of the University of Alabama School of Law. It covers incidents, developments, and personalities concerning the deanship of Albert Farrah, which began in 1913. This post is the second in a series designed to carry us through the highlights of 150 years of Law School history. In this series we shall employ several authors, who will focus on either chronological or topical approaches to the issues at hand.

A.J. FARRAH, FROM MICHIGAN TO ALABAMA

Dean Albert J. Farrah was born in Adrian, Michigan in 1863, and died in Tuscaloosa in 1944, a few days short of his eighty-first birthday. He received his education at Adrian College and at Cornell College in Iowa, after which he taught school and was Superintendent of Schools at Michigamme, Michigan. In the meantime he studied law at the University of Michigan. He received his LLB from Michigan in 1896 and practiced in Ann Arbor for several years while teaching at the University of Michigan as an instructor.[1]

In 1900 Farrah embraced an opportunity to move south to Deland, Florida, where he was the founding dean of the Stetson University School of Law. In 1909, “he was called to the University of Florida, where he again founded the school and became Dean and Professor of Law.”[2] There is no doubt that Farrah’s teaching style was challenging, probably in the best Socratic fashion. The editors of Stetson’s 1909 yearbook, the Orange Thorn, quoted him as having warned his senior class that “the law is a jealous mistress”—an old saw worked to death by most law professors of the time. Farrah, however, apparently meant what he said. Speaking of the senior class, the editors observed that “of all those who have paid court only three have proved sufficiently faithful to satisfy her jealous demands and present themselves as candidates for her reward, . . . duly approved by her lawfully constituted agent, A.J. Farrah.”[3]

In 1912 the University of Alabama’s president, George H. Denny, invited Farrah to come to Tuscaloosa as a law professor. A year later the law dean William Bacon Oliver resigned to run for congress and Farrah was named dean of the law school. The two men, Denny and Farrah, would work together for much of the following three decades. It was a productive arrangement, for both men shared the common goal of making Alabama one of the best schools in the south.[4]

STUDENTS, FACULTY, AND CAVEATS: EARLY YEARS, 1913-1920

One measure of Farrah’s success was the continued growth of law school enrollment. From 139 students in his first year as a professor the number of law students rose to 277 in the academic years 1934-1935.[5] Farrah, however, was concerned about more than rising numbers; his focus was also about law students as individuals. He remarked, long after the fact, that the “friendship and support” of his students was crucial to his success in “that hard first year of service” and afterward.[6] Given this closeness to the students it should be no surprise that Farrah’s emphasis was not just about developing “sheer intellectual brilliance.” His colleague and successor William Hepburn wrote that Farrah “wanted the Law School to produce its share” of great intellects; but he was “just as interested in the average student, even the poor student,” and “nothing “delighted him more than to discover that some student he had at one time contemplated dropping from school for poor work had made a success at the bar.” Hepburn noted that Farrah also concerned himself with “standards of ethical practice, and he gave much thought to questions of legal ethics.”[7]

Farrah was an excellent classroom teacher—though, as the 1916 Corolla put it, his use of the Socratic Method made him “the terror of those unfortunates who happen to be unprepared.”[8] Still, his students saw him as more than just an academician. In dedicating the 1917 Corolla to Farrah, its editors remarked upon his “faithful service,” his “ability as an instructor and his high character as a man.”[9]

There is no doubt that Farrah was something of a wonder-worker at the School of Law, but we should remember that the times in which he lived imposed considerable limitations upon his larger impact. By a combination of law and custom, two large demographic groups were drastically underrepresented at the School of Law. The school had admitted two female students prior to Farrah’s arrival: Luelle Lamar Allen, who graduated in 1907, and Maud McLure Kelly, Class of 1908.

Indeed Kelly, who had graduated third in her class, was already a successful practitioner by the time Farrah came to Tuscaloosa.[10] But Farrah did not profit by considering her example. Female students studied law during his deanship in ones and twos.

Even more rigidly, Alabama schools and colleges were segregated by race during Farrah’s entire tenure (and for decades before and after). African-American school children were prohibited by law from studying alongside white children, and while the laws governing college students were much less specific—the 1907 Code contains no reference to race in the laws pertaining to the University of Alabama—still the custom of exclusion was firmly in place.[11] For much of the first half of the twentieth century, the state offered no professional legal education for African Americans.[12] Thus Farrah, like nearly all white educators, played his part in a situation little removed from what one scholar has called the “nadir” of American race relations.[13]

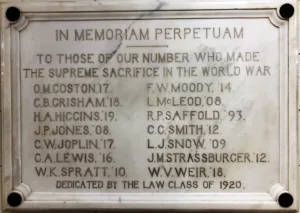

When Farrah took over the deanship, the Law School had one other professor, Adrian S. Van de Graaff, and “two part-time lecturers.” Farrah quickly added another full-time faculty member, Edmund C. Dickenson, whom he had known at the University of Florida. The law faculty was in a state of flux during the late 1910s and early 1920s—the World War and its aftermath were largely to blame.

But by the mid-1920s Farrah presided over a faculty of five full-time law professors and a part-time staff that featured a future Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court.[14]

STUDIES, PUBLICATIONS, AND ACCREDITATION, 1920-1928

As early as 1920-1921, Farrah and President Denny worked successfully to persuade the University’s Board of Trustees to approve a three-year course of study, bringing the Law School up to what was increasingly the national norm. This move “permitted expansion of existing courses, particularly Property, Torts, and Equity, and the addition of new ones, including Practice Court and several electives.” These courses were taught by the “case-study technique,” which required students to use casebooks and brought them under the Socratic gaze of their professors. The 1920s also saw the launch of the school’s first scholarly journal. After some time spent in planning, the Alabama Law Journal was first issued in October 1925, edited by a panel of faculty members. The decade also saw the beginnings of national legal fraternities and other law-related clubs at Alabama, including the Somerville Literary Society, founded in 1924.[15]

By the 1920s, University of Alabama law graduates were making a name for themselves, which was reflected in the state legislature’s 1923 renewal of the “diploma privilege”; this allowed UA Law graduates admission to the bar without sitting for a bar exam.[16] In the meantime, Farrah pursued the goal of American Bar Association membership. By 1922, the ABA had required its members to maintain a three-year program of instruction—already in operation at Alabama—and had mandated that its members require two years of college as a necessary preliminary to law school admission. At the urging of Denny (and Farrah), the UA Trustees approved the new admissions standard in 1926. Clearing this second hurdle was sufficient, and in 1926 the ABA placed the law school on its list of approved law schools. After two years’ probationary membership, the Law School was accepted into membership in the Association of American Law Schools, the legal academy’s highest degree of accreditation.[17]

THE CROWN JEWEL

To Farrah, the only missing element of the Law School was a proper setting. Since the beginning of his tenure, the school had been housed in Morgan Hall, an attractive, recently constructed building; but it was but hot in the summer, cold in the winter,[18] and generally cramped.[19] President Denny agreed with Farrah, and starting in 1920 he made construction of a new law school building a priority project.