Ephemera from an 1898 Congressional Campaign

- March 31st, 2016

- by specialcollections

- in Collections, Preserved in Amber, Recent Acquisitions, Unique or Annotated Works

Editors’ Note

This post represents the second installment in a new category that we hope will be an occasional feature of our blog. Posts in this category will feature materials that are unique in some way, perhaps through ownership, creative attachment or insertion of documents, or other unusual items. Our previous post, “Next to His Bible”: John Randolph Griffin’s copy of the Louisiana Civil Code was the inspiration for this category that we have titled, Preserved in Amber. Our current post features an interesting small collection that is described by Hudson Cheshire, a 2017 J.D. candidate at the University of Alabama School of Law.

Ephemera from an 1898 Congressional Campaign

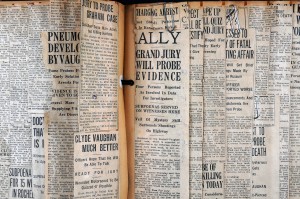

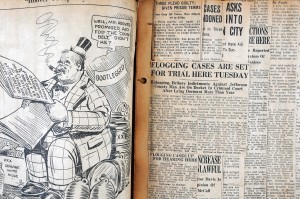

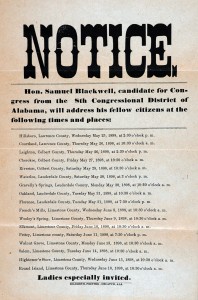

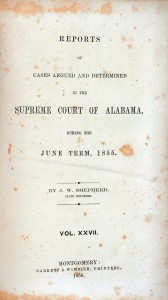

The topic of this post is a recently acquired collection that offers a glimpse into the life of a small town politician in early 20th century Alabama. The collection includes a copy of Alabama Reports Volume XXVII (the Alabama Supreme Court cases argued in the June term of 1855), and three documents that were laid within its pages. Two of the documents are laundry receipts for one Samuel Blackwell. The third is a notice for a series of events where Blackwell would be speaking in his 1898 campaign for Congress.

Samuel Blackwell, the subject of the laundry receipts and political flyer, lived from 1848 to 1918 and is buried in the Decatur City Cemetery. While history has relegated Blackwell to obscurity, the sparse documents that remain suggest a man of relative political success in his place and time.

Blackwell began his career in public service early, enlisting in the Confederate Army at fourteen years old. By his fifteenth birthday, he was a prisoner of war in Camp Douglass, a large Union prisoner camp in Chicago. Years later, as the Morgan County delegate for the Constitutional Convention of 1901, Blackwell recounted a comrade’s sardonic description of the conditions at Camp Douglass: “We slept until after breakfast, skipped dinner, and went to bed before supper.” [Journal of the Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Alabama, 1901, 3025].

A document from 1903 indicates that Blackwell served at least one term as mayor of New Decatur in the early twentieth century and in the 1910-1912 Biennial Report of the Attorney General of Alabama, Samuel Blackwell is listed as the  Solicitor for the Morgan County Law and Equity Court. Perhaps the only lasting glimpse into Blackwell’s perspective comes from his words at the 1901 Constitutional Convention, preserved in the Official Proceedings. Describing the Convention’s atmosphere of pessimism regarding the voting capacity of the general population, historian Sheldon Hackney quotes Blackwell saying, “nature has marked the weak and incompetent to be protected by Government, rather than to be the directors of the Government.” [Populism to Progressivism in Alabama, 196].

Solicitor for the Morgan County Law and Equity Court. Perhaps the only lasting glimpse into Blackwell’s perspective comes from his words at the 1901 Constitutional Convention, preserved in the Official Proceedings. Describing the Convention’s atmosphere of pessimism regarding the voting capacity of the general population, historian Sheldon Hackney quotes Blackwell saying, “nature has marked the weak and incompetent to be protected by Government, rather than to be the directors of the Government.” [Populism to Progressivism in Alabama, 196].

Had Blackwell been successful in his 1898 campaign for Congress, he would have been better remembered in Alabama history. Nevertheless, available records merit the assumption that Blackwell was an influential political figure at the turn of the century, if only in his own small corner of the world.

Hudson Cheshire, Research Assistant, Bounds Law Library