Book Note: Civil War Alabama by Christopher Lyle McIlwain, Sr.

- August 22nd, 2016

- by specialcollections

- in Book Notes, Guest Contributors

The editors of Litera Scripta have taken pleasure, over a number of years, in talking about Alabama’s Civil War and Reconstruction with University of Alabama Law School alumnus Christopher McIlwain. Throughout many conversations and exchanges of emails, we have been impressed at the range of Chris’ knowledge and astonished at the all-inclusive scope of his research. It was clear to us that his book, when published, would be an original contribution to Alabama history. Specifically, Civil War Alabama is a long-overdue assessment of Alabama Unionists, a surprisingly numerous group whose fate has hitherto been either to be maligned or to be ignored. In this connection we are delighted to publish a second book note by G. Ward Hubbs of Birmingham-Southern College, author of Searching for Freedom after the Civil War: Klansman, Carpetbagger, Scalawag, and Freedman.

Civil War Alabama

By Christopher Lyle McIlwain, Sr.

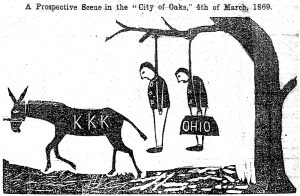

Generations of Alabamians have had but one account of the Civil War in Alabama: Walter Lynwood Fleming’s 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. While those steeped in the Lost Cause found it reassuring, even uplifting, modern readers and especially historians blush. Oddly enough, the war itself is but the opening act for Fleming’s real interest: Reconstruction. The first 57 pages of Fleming’s tome are devoted to the sectional crisis and secession; the war engages 186 pages; and an extraordinary 552 pages, the rest of the book, is spent painstakingly detailing the atrocities said to have been committed on white Alabamians during Reconstruction. Fleming’s topical approach—which highlights certain events while de-emphasizing, obscuring, or even omitting others—allows him to pick and choose how the former Confederates (nearly all the white population, according to him) endured those years at the hands of an oppressive occupying government. That Alabama’s citizens were overwhelmingly united in supporting the Confederacy is taken as a given. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama may be the most emblematic example of the Dunning School (named for William A. Dunning of Columbia University, Fleming’s graduate-school professor) that held sway nationally during the first half of the twentieth century. And it held sway in Alabama for even longer as no one has published a comprehensive study challenging Fleming’s interpretation.

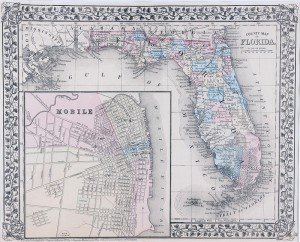

After over two decades of careful research into primary documents, Chris McIlwain’s Civil War Alabama could not be more different from Fleming’s Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. To begin with, McIlwain does not present the war topically but rather as a narrative—warts and all—from William Lowndes Yancey agitating in Montgomery to Mayor Robert Slough surrendering in Mobile. The result is more complex, even, than we might have expected. McIlwain, himself a lawyer, points to the crucial role that Alabama’s bar played in moving the state towards disunion. He also amasses indisputable evidence regarding the centrality of the institution of slavery in the decision to secede. McIlwain’s narrative approach becomes especially important in tracing the war itself because it allows him to integrate political, economic, social, and military events in ways that Fleming never could or would. We see repeatedly, for example, how home front morale fell with battlefield reverses and economic losses. But lukewarm support for, and even antagonism towards, the Confederacy did not begin with battlefield losses or the confiscation of crops.

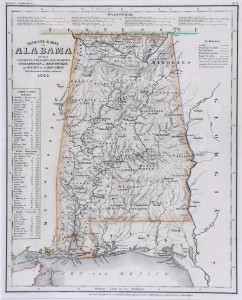

This point is crucial and represents the book’s main contribution. McIlwain wisely refuses to estimate exactly how many Alabamians were committed to the new government and how many were not. Support and resistance was constantly shifting. About 40 percent of the Secession Convention were Unionists—a fact disguised by their adoption of the name “Cooperationists.” While Fleming and others insist that Cooperationists were mostly just go-slow secessionists, McIlwain reminds us that the term had been used by those who in 1850 resisted secession and that in 1861 the out-and-out secessionists saw no difference between Cooperationists and Unionists.

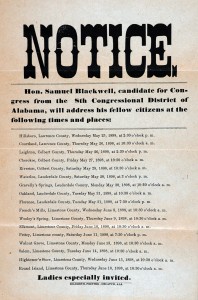

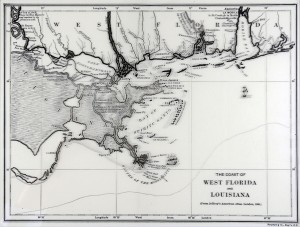

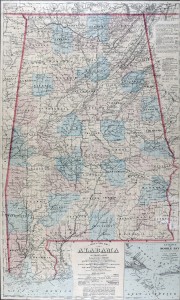

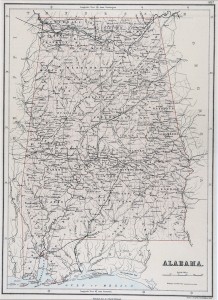

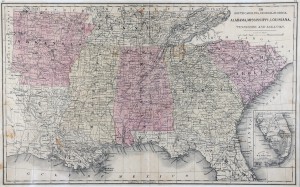

Confederate fervor soared after the bombs fell on Fort Sumter, yet early Confederate victories did not kill Unionism. Far more than previously acknowledged, a significant portion of the citizenry consistently opposed those who took over the state government and held power for those four years. And that opposition was not confined to isolated Winston County farmers. Dissenters were to be found throughout the state, from the Shoals to Mobile Bay, from the Tombigbee to the Chattahoochee. They were to be found in every profession, from farmers to judges. And they were to be found in every economic stratum, from poor to wealthy. At times it was as if two civil wars were being fought in Alabama. The campaigns would be led in the newspapers by the “generals of the press” as well as on the battlefields by the generals of the armies; the battles would be waged with ballots as well as with bullets. Pleas for peace were made privately as early as 1861 and became increasingly public as the death toll mounted and Union victories in Alabama’s sister states created intense fears of destructive invasions. “The war was very popular,” remembered a west Alabama minister, “until the coffins began to come back from Richmond.” After McIlwain places Alabama’s peace movement in its proper context, he explains its failure to extract Alabama from the war. And he posits the multiple lost opportunities open to Confederate leadership that might have averted destruction of the state’s industrial base and railroad infrastructure—opportunities that came even after Confederate independence had obviously become a hopeless cause.

In discussing the many factors that raised and lowered Alabamians’ morale, McIlwain deftly integrates military events, shortages, inflation, and human loss with passages from letters, diaries, and newspapers. His detailed documentation, which amounts to over a third of the book, represents only a part of what he originally included but had to edit out in order to make the book accessible. A great many of the extant sources about Alabama Unionists have never been used. These new sources generally fall into three categories: articles in out-of-state newspapers or other publications, letters written to individuals living in the North, and materials republished (in southern or northern journals) from Alabama newspapers that were not preserved.

That others have not used these sources raises a tantalizing question. Why, if Unionism was as strong as McIlwain makes it out to be, did it take this long for the evidence to emerge? Although McIlwain does not discuss it in his book, he is convinced that former Confederates intentionally eliminated materials that criticized the Confederacy, the war, or Democratic government. In-state newspapers during the war scarcely mention the Peace Party or troubles with motivation. And I myself have yet to find copies of Republican newspapers printed in Tuscaloosa during Reconstruction, although they probably enjoyed a healthy readership at the time.

If indeed the lack of in-state sources for Alabama Unionism are largely, as he believes, the result of deliberate acts of elimination, then that raises yet another question: Why? Why go to all the trouble of suppressing the record? The answer: To avoid Responsibility. Surely blame for those dead, the untold suffering, and the state’s disastrous economic downturn should not be directed at the Democratic Party and its hothead lawyers? All white Alabamians were in it together, surely? And indeed the defense of the state was a noble, if lost, cause. When all are guilty, then (in practical terms) none is to blame.

But Alabamians were divided, and not united, in leaving the Union and fighting the war. And they would reconstruct Alabama as a state no less divided. Responsibility cannot so easily be cast off.

G. Ward Hubbs

Birmingham-Southern College